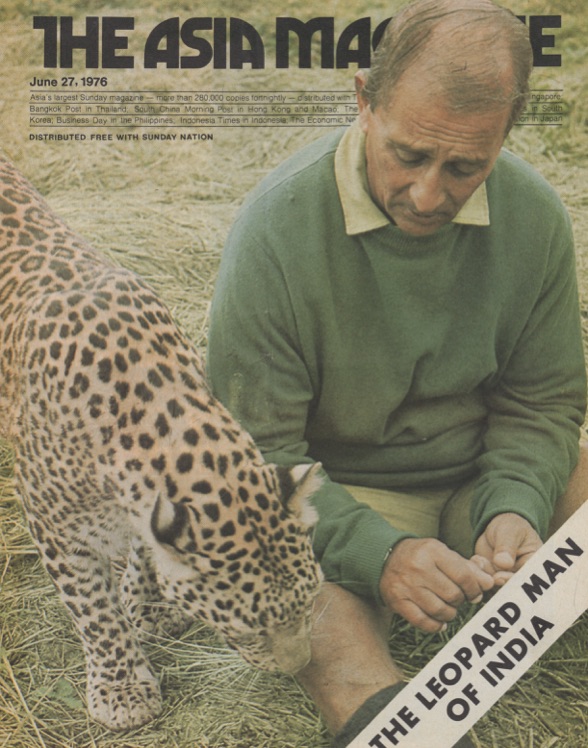

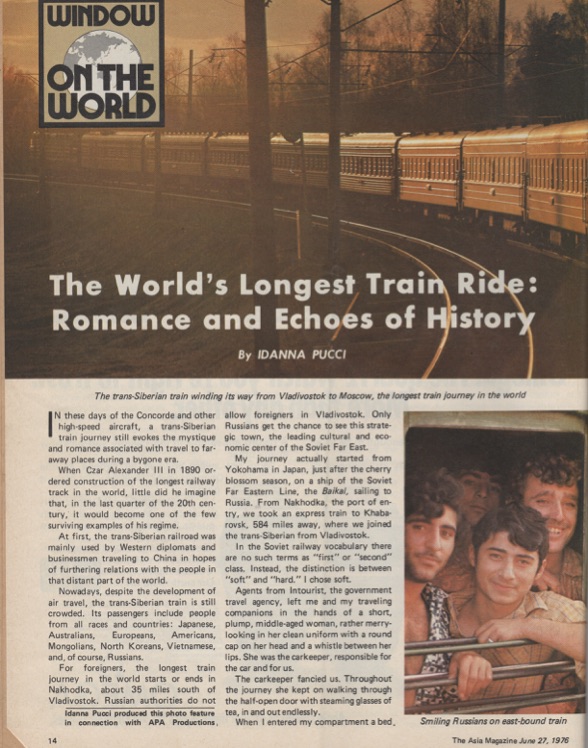

In these days of the Concorde and other high-speed aircraft, a trans-Siberian train journey still evokes the mystique and romance associated with travel to faraway places during a bygone era.

When the Czar Alexander III in 1890 ordered construction of the longest railway track in the world, little did he imagine that, in the last quarter of the 20th century, it would become one of the few surviving examples of his regime.

At first the trans-Siberian railroad was mainly used by Western diplomats and businessmen traveling to China in hopes of furthering relations with the people in that distant part of the world.

Nowadays, despite the development of air travel, the trans-Siberian train is still crowded. Its passengers include people from all races and countries: Japanese, Australians, Europeans, Americans, Mongolians, North Koreans, Vietnamese and, of course, Russians.

For foreigners, the longest train journey in the world starts or ends in Nakhodka, about 35 miles south of Vladivostok. Russian authorities do not allow foreigners in Vladivostock. Only Russians get the chance to see this strategic, cultural and economic center of Soviet East.

My journey actually started from Yokohama in Japan, just after the cherry blossom season, on a ship o the Soviet Far Eastern Line, the Baikal, sailing to Russia. From Nakhodka, the port of entry, we took an express train to Khabarovsk, 584 miles away, where we joined the trans-Siberian from Vladivostok .

In the Soviet Russian railway vocabulary there are no such terms as “first” or “second” class. Instead, the distinction is between “soft” and “hard”. I chose soft.

Agents from Intourist, the government travel agency, left me and my traveling companions in the hands of a short, plump, middle-aged woman, rather merry looking in her clean uniform with a round cap on her head and a whistle between her lips. She was the carkeeper, responsible for the car and for us.

The carkeeper fancied us. Throughout the journey she kept on walking through the half-open door with steaming glasses of tea, in and out endlessly.

When I entered my compartment, a bed had been prepared. The mattress was covered with an immaculate white sheet; white pillowcases were fitted in cushions; a warm blanket had been slipped into a kind of double sheet sewn on the sides in sleeping-bag style. The floor of the compartment was carpeted. All one needed to do was to say “chai” and hot tea straight from the corridor’s samovar, was brought by the carkeeper.

In the hard class, I found out later, things were quite different. The bed wasn’t made and the passenger had to pay extra for mattress and sheets. Tea had to be taken in the dining car and the floor was bare.

I decided to decorate the compartment – after all, it was going to be our house for the following week! I covered the mattresses with old, flowery materials I had bought in Japan. I lined up a few books: some Russian novels, a copy of an old National Geographical article on Leningrad, a guide to the Soviet Union, and two or three mystery books. Then drinks: vodka and whisky. Finally, there were flowers I had bought from an old woman who was shyly and illegally selling them behind a wall at the station.

In the middle of nowhere we stopped at a small town called Smidovich. There I was told that we had entered the region of the Semi-Autonomous Jewish Republic. Only much later in the journey did I learn that in 1928 the Russian government had set aside that thickly forested region for colonization by the Jews.

The stop in Smidovich lasted 10 minutes. Then we came to Birobidzhan, the capital of the region, where we stopped for only four minutes. The first engine change took place in Bira, another town, where 10 minutes were allowed.

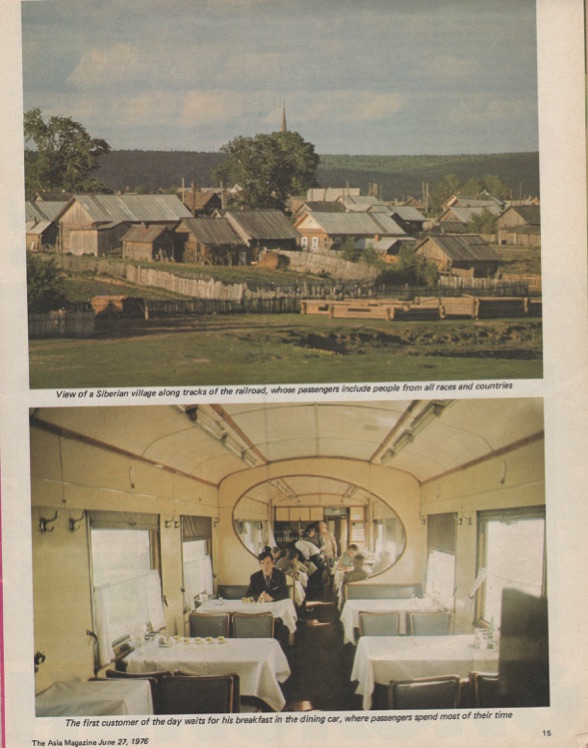

Invariably, during such waits, one would get down and walk up and down the platform. Most of the Russian men never seemed to quit their dark navy pajamas; the longer the stops, the more they would walk about in them while queues of people were forming to buy bottles of delicious yoghurt, loaves of bread and thick sausages from the small stalls.

That afternoon a little Russian girl named Marsha made friends with Michael and Richard, the children of an English doctor who, after three years’ practice in Fiji, was going back to England with his family. They occupied the compartment next to ours, while Marsha and her grandmother were settled in the one beside them.

Marsha loved to run up and down the corridor, and that’s where the three children met. For days they kept passing an old puppet-monkey at each other. There were no barriers between them, not even that of language. They were not yet questioning life situations and other serious matters.

Three fat, tough women kept the dining car running non-stop from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m. They dealt with drunken soldiers, sailors, and hustlers as if they were flowers in full bloom. Even the strongest men seemed intimidated b those women, whose presence in the train was essential. The dining car was in fact the place, where the people spent the most time. Breakfast, lunch and dinner were massive affairs which, especially for the Russians, lasted hours. In the morning the car looked neat and every white tablecloth was spotless. By the evening it looked like a zoo.

One morning a strong, burly man knelt over our table. He didn’t sit down because there was no place left. He talked loudly, addressing himself to us. Nobody could understand him. He touched my shoulder and smiled while trying to keep his balance. He was looking and pointing at me. He then filled up with champagne all the empty glasses he could set his eyes on. His hands were worn out with work, flattened by weight of hard years. He continued to look at me obsessively.

After kissing me on the cheek, the man left. For him and many of his fellow travelers, the trans-Siberian journey was one great feast. People passed like visions in the corridors, leaving behind the echoes of their talking and singing.

A fair, neat-looking Russian officer stopped in front of our compartment. I heard him making conversation with one of my traveling companions, an old-fashioned Australian.

The officer spoke fluent English, so I joined the conversation. The Australian was a passionate musician and had started a jazz orchestra in Adelaide, where he lived. So music was discussed. Names like Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley were mentioned. The discussion had a strange quality about it: the officer knew more than we did, but tried to hide his knowledge. He told us that he had studied English in Moscow, and that he had worked as an interpreter before joining the army. His accent was so British that it made us wonder.

He said that any Russian was free to go abroad as long as he had enough money, but that international travel was too expensive for most people. Then he looked at me and said: “Tell me, what about the hippies? It’s finished, eh? They didn’t find what they were looking for?”

His ironic tone made me laugh, “I don’t know,” I replied.

He ignored my answer and went on to speak about the shows “Hair” and “Jesus Christ Superstar.” Then, smiling, he started to hum the “Superstar” tune. Soon he said good-bye and moved on, holding under his arm a copy of Esquire magazine and a Harold Robbins novel.“You should know. You seem to know everything.”

Time went on and on, entirely void of meaning. One day melted silently into the next. Siberia was enfolding itself like the pages of a valuable picture book left in the wind. Mongolia and Manchuria bordered the horizon.

Later that morning we arrived in Chita, a picturesque town on the slopes of the Yablonovy Range. Chita and its region had been the earliest in Siberia to be settled. In 1653 the Cossacks built the first stockade there; in 1825, it gained fame as the place of exile of the Decembrists, the group of noblemen who attempted a coup in St. Petersbourg, now Leningrad, against the czarist regime. In 1849, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, charged with being a member of a revolutionary group, was sent to Chita -where he served four years of hard labor and wrote The House of the Dead.

Chita, too, has lost its identity. Once the Bolshevisik capital of Eastern Siberia, it is, nowadays, just another interval along the trans-Siberian route.

The train moved on. Soon, horses were grazing on open expanses of grassy land. The earth had become dark. We were in fact moving across the much-celebrated steppes, so often painted by Russian artists and described in famous books.

Soon a second engine was attached and the 18 cars of the train made their way up into a solitary plateau of steam, clouds and mountains, at 4,000 feet high. I thought of the people traveling with me in the same car – nearly all of them foreigners like myself, but many Russians too. I felt I knew many of them and that I would remember their faces for a long time, even if no words had passed between us. I thought about them because they were so much part of what was happening.

We had started together. We continued together. We were all strangers to each other, and yet we shared something that was beyond sleeping, waking and washrooms.

In the middle of the night train came to a stop in Ulan-Ude, the town known to Mongolians as The Red City. From there, a railroad link cutting off towards Nanshki on the Mongolian border, then joining the Chinese railway, made its way to Peking. From there also on a highway led to Ulan-Bator, the capital of Mongolia.

A few minutes later we were moving on; at dawn into the world’s deepest lake, the Baikal, appeared in between the mountains. The Angara River was running beside us.

Irkutsk, the capital of Siberia and renowned place of banishment for exiles, finally came in sight, marking the halfway point of our journey. I could see the silvery Angara flowing by several huge, modern apartment buildings as the train pulled into the station early in the morning.

Trees, lakes and streams followed one another. After Krasnoyarsk, the train covered long distances without stopping. The steam engine had been replaced by an electric one, so water was no longer needed. Late at night the “Chicago of Siberia” better known as Novosibirsk appeared with its thousands lights.

The train wound its way up the rocky Urals and then descended to Petropavlosk, a market town for caravans coming from the steppes of the south. Then it was Sverdlovsk, in the middle of a vast plain. Once called Yekaterinburg, this town also had its story.

It was in Sverdlosksk that Czar Nicholas II went into exile in 1918 with his family. They lived in captivity in a building called “The House of Special Purposes”. One day they were ordered to descend into a room in the basement, where they were shot and bayoneted. Their bodies were taken into the woods nearby, burnt and thrown down a mineshaft.

My eyes shifted to those woods that now were hedging the railroad. Suddenly a sign, barely noticeable on the side of the track, brought my attention back to the journey. It bore two arrows pointing in the opposite direction and two names: Asia, Europe.

Tomorrow Moscow. Tomorrow the journey would end. Our bags would have to be packed. Books, empty bottles of yoghurt or whisky, everything would have to be discarded or put away.

A florescent spring woke me up. Fields were now lined with bright yellow flowers as if the train had entered the private domain of a Vivaldi revelry. Now the train passed through fairly large towns without stopping.

In the dining car people sat freshly washed, dressed, combed and shaved, as if ready for a wedding. Nothing was left to eat. Only a few bottles of vodka stood on the shelf next to the counter. Corridors were jammed with suitcases and packages.

Moscow’s first apartment buildings were now beside the rail track. The train gave out a long blast announcing its arrival. Outside were streets with cars and people crossing them at traffic lights.

The highest tower in the world, Moscow’s TV and radio station, stood out with its antenna in the sky. A sense of exultation had replaced excitement. Minutes seemed to last forever. I wound my watch: 11:50 a.m. Time took its shape and form again. The train gave out another blast. Then it slowed down smoothly, softly, gently until it went so slowly that one could have walked beside it. Finally at noon the engine stopped.

Yaroslavl station seemed more like a station in some romantic, fashionable resort of the turn of the century than a station in the present-day capital of the Soviet Union. What made it so was the Czarist elegance of its architecture with rows of polished silvery pillars running.

In line, one behind the other, we waited in the corridor, for our turn to get out. The Intourist agent climbed on the train accompanied by porters. Our names were called out loudly.

“Yes…” each of us said in acknowledgment. The agent told us to follow him, and we did. Our journey on the trans-Siberian railroad was over.