“Going back at least nine thousand years to the early agriculture of the Near East and Old Europe, we have a tradition of the power of the Goddess and of her child who dies and is resurrected—namely, it is we who come from her, go back to her, and rest well in her. This tradition was carried through the cults of ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and down into the Classical world, before finally delivering the message into Christian teaching.”

Joseph Campbell, The Goddess: Mysteries of the Feminine Divine

The Goddess that Joseph Campbell mentions can be found in the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata (of the holy Annunciation) in the heart of Florence. Originally a simple farmhouse surrounded by woods, it once lay two hundred yards outside the medieval city’s northern wall. During the terrible siege by the German Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, in 1081, his mercenaries launched daily barrages of arrows. The city wall suffered tremendously yet did not fall. In memory of that resilience, the farmhouse was transformed into a sacred place of prayer.

It is here that the “Servants of Maria” —bound by a vow of poverty and a burning desire to help the afflicted and sick—founded their order. The legend goes that these seven Florentines had been overcome by a vision of the Virgin in the forest, and slowly they built a small church devoted to the Holy Mary, and a convent.

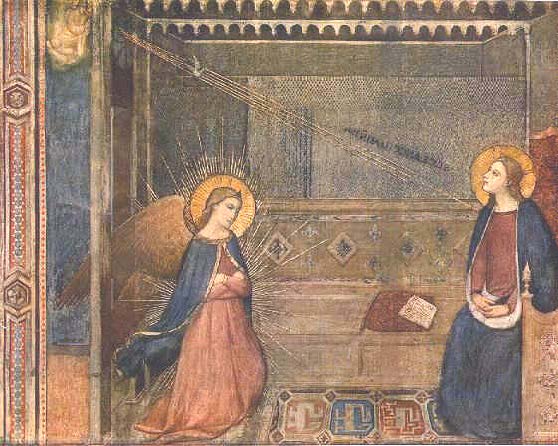

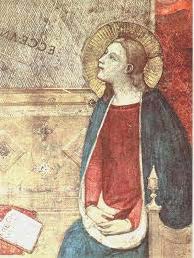

In 1252, they asked Fra’ Bartholomew, the artist among them, to paint the scene of the Annunciation for their new church. But the friar was tormented by the fear that he would not do justice to the young Virgin’s beauty. Exhausted after so many attempts, he fell asleep in deep despair.

When he woke up, he could not believe his eyes when he saw that Mary’s face had been painted. Clearly, no human hand had done this. Only an angel could have created such beauty. And from that day, the fresco has been known as the “Miraculous Annunciation.”

Word of the miracle spread far and wide. Even the great Michelangelo confirmed, “it was not through the art of painting that the face of the young Virgin was created. It is truly divine.” He was right because until then, the Madonna had always been depicted in a stylized Byzantine manner, without overt emotion. But here was a simple teenage girl filled with serene wonder and awe.

Soon, houses surrounded the church as people wanted to live near the place where the miracle had happened. A new outer circle of walls was then built, placing the church inside the city.

Over time, the little church grew into the revered Basilica della Santissima Annunziata, where the Florentine cult of the Madonna flourished over the centuries. By 1447, the Servants of Mary, under the patronage of Piero, the son of Cosimo dei Medici, erected a magnificent shrine for the miraculous painting.

Over generations, great artists such as Beato Angelico, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo and Leonardo would all paint their own version of the Annunciation, a theme that was always the most challenging and closest to their hearts.

Entering the Basilica today, you will find the divine fresco in its splendid shrine on your immediate left. The Mother Goddess remains so adored and her magnetic pull is so strong that you will see worshippers seated on pews that are all turned to face her. In fact, this is the only church in Christendom where parishioners deliberately turn their backs to the altar, so they may face the divine feminine force. And today, her presence still exudes the promise of fertility. Each and every Florentine bride comes here on her wedding day to place her bouquet of flowers as an offering to the Madonna

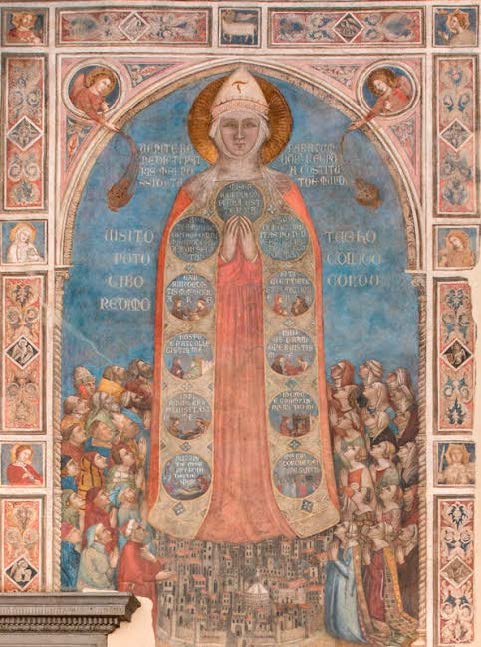

The resurgence of the Goddess as “Mother Earth” that rose like a phoenix during the Renaissance began with this fresco, but also included another fresco found inside a building not far away just across from the Baptistry. Known as Loggia del Bigallo , it housed the famous Madonna of Mercy (shown below) painted by Bernardo Daddi in 1342. At that time, the when the Bigallo was the headquarters of the confraternity dedicated to transporting the city’s sick to hospital.

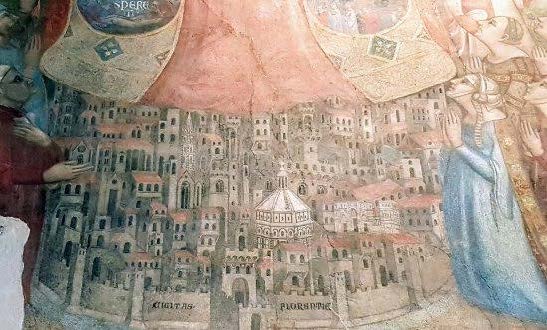

Few know that the Madonna of Mercy later inspired Brunelleschi’s dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Flower. For over a century, the powerful, wealthy wool guild had waited for the right architect to appear for the dramatic project of erecting the dome.

Comparing the fresco and the cupola, one can see how Florentines viewed the terracotta dome as the all encompassing red cape of the Madonna protecting the entire city below, offering her compassion to all.

The symbolism behind the dome’s shape and the fresco is rich and deep: the citizens of Florence, crowded around the Madonna, look up to her as their “ultimate Mother”. Her cape encloses all the works of mercy in descending spheres. These acts, cited in Matthew 25, were the cornerstone of the city’s philosophy of behavior – feed the hungry, give water to the thirsty, shelter the homeless, clothe the naked, visit the prisoners, help the sick and bury the dead.

This ethical fabric protected the city’s most vulnerable and was bound by strict regulations in each of the numerous guilds that together controlled the vibrant economy and social order of Florence. Works of compassion were acted out daily in the “Mother’s spirit” under her watchful eye in the birthplace of humanism.

The Madonna became the divine symbol of the Florentine Renaissance and, through her beauty, transformed Western art. During that groundbreaking epoch, young Mary was always portrayed in an earthly paradise, a heavenly garden and then as a sublime mother with her newborn child. Nature blossomed with Spring’s fertility.

With the flush of Neo-Platonic syncretism (that arrived from Constantinople and Alexandria), the young mother would later be portrayed as the Venus by Botticelli and even as Isis, the Egyptian Goddess of the Nile by Pinturicchio.

Five centuries later in 2016, Pope Francis visited Florence during his Jubilee devoted to the theme of “Mercy”. On that special day, after celebrating Massa in the Duomo, the Holy Father walked through the large chestnut doors of the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata. For the Jubilee, these two sacred places of worship, dedicated to the Madonna. had opened their holy doors or porte sante, offering every worshiper that also crossed that threshold full blessings and redemption as if they had walked through the holy door of St. Peter itself in the Vatican. No other Florentine churches held this honor.

Pope Francis clearly appreciated the Florentine reverence to the Madonna. After all, his revolutionary Encyclical, Laudato Si, enshrines our “Mother Earth” on its very first page, and laments how she has been abused and violated by her children. His plea calls for all of us to take care of our sacred mother, our common home. And, when Pope Francis came to Florence, he prayed to the “Holy Mother”.

Her figure of feminine compassion and mercy has served as a civilizing force in the Western World. The veneration of the Madonna forged in that small Florentine church one thousand years ago elevated art, culture, and humanity far beyond the patriarchal views of medieval Rome, giving birth to the bold Renaissance vision to protect, empower, and elevate Florence’s citizenry, while beautifying their “city of the flower” for future generations to come.