The Night of the Deluge

It is November 3, 1966, a terrible wind is blowing over Tuscany. It has been raining several days but a three-day holiday is coming up, the Feast of Army, the city is decorated with the three colored flag of Italy and the red lily of Florence. The shop windows gleam with Christmas lights. Now, toward evening, a long cue of cars winds itself to the toll booths spaced along the highways.

There is alarming news coming in from nearby villages – torrential rains have washed out bridges, flooded valleys, covered roads with mud. The River Sieve, flowing into the Arno is swollen as it has not been in years. The water at the two colossal dams in the Valley of Hell is now 167 meters high and the only way to save the dams is to open the safety doors.

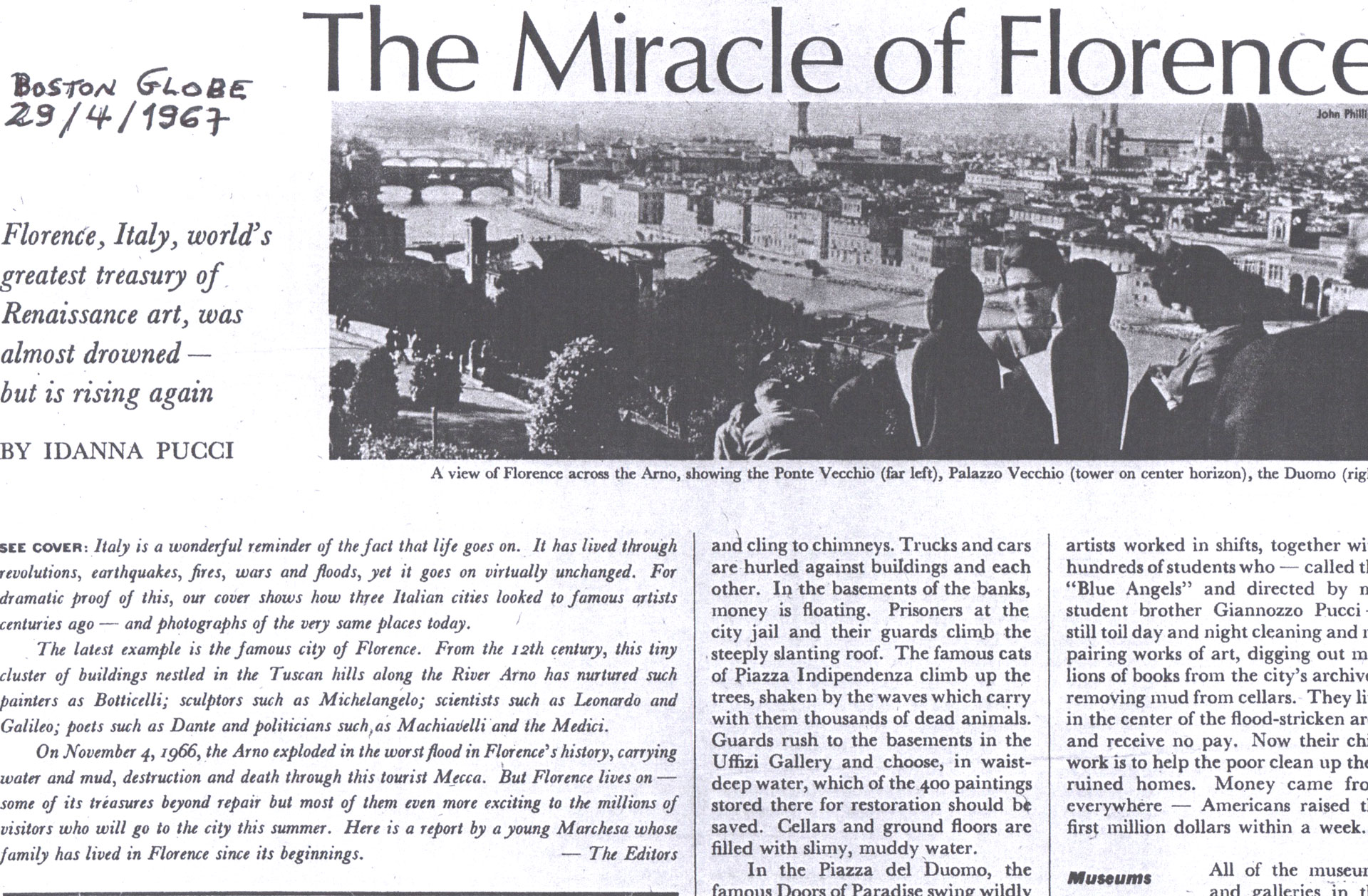

A gigantic wave bursts out with terrific force. The Ponte Vecchio – the Old Bridge – is hit under the eyes of the Genio Civile engineers who have left their cars in a neaby street and will never find them again. It is two a.m.. A decision is made not to ring the bells of Palazzo Vecchio as in the Middle Ages, for fear the citizens will rush out and be swept away. Only the jewelers of Ponte Vecchio are alerted and they rush to save what they can.

The city is plunged into chaos

It is four a.m. and the bridge is shaking but holding. Trees have pierced it like swords, smashing windows and carrying in their wake all jewels, leather goods and silver the shopkeepers have not saved. The mayor tries to telephone the civil engineers office, but the line is down. Florence is plunged into darkness and chaos.

At six a.m., the river bursts over its embankments and 250 million cubic meters of water and mud rip through the city at 50 miles an hour. The century-old sewers burst open. Racehorses break loose at the Cascine. Oil furnaces burst open and the oil joins the water and mud to smear with black the façades of Renaissance buildings.

On the rooftops people wave sheets and cling to chimneys. Trucks and cars are hurled against buiildings and each other. In the basements of the banks, money is floating. Prisoners at the city jail and their guards climb the steeply slanting roof. The famous cats of Piazza Indipendenzaclimb up the trees, shaken by the waves which carry with them thousands of dead animals. Guards rush to the basements of the Uffizi Gallery and choose in waste-steep water, which of the 400 paintings stored there for restoration should be saved? Cellers and ground floors are fille dwith slimy, muddy water.

In Piazza del Duomo, the famous doors of Paradise swing wildly until five of the golden panels fall off. The water rushes in to change Donatello’s statue of Magdalena into a mass of mud. Manuscripts, documents and priceless books in the National Library are drowned. A colossal wave breaks open the door of the Ghirlandaio Chapel and completely destroys the frescoes. In the Archeological Museum, famed for its Etruscan art, the floors have caved in. Helicopters pluck people form rooftops.

At seven p.m. s, the stars appear. The water starts to recede. Prisoners return to their jail cells. The homeless take refuge into the Palazzo Vecchio. The anguish is over – and just beginning.

Florence Fights Back

Today, not quite six months after the disaster, Florence is ready for the world to see. Thousands of people from every country rushed to the ruined city to help dig out and clean up. Many more sent money. Restorers, doctors, technicians, diplomats, engineers, architects, scientists, artists worked in shifts, together with hundreds of students – called “the Angels of the Mud” and directed by my student brother, Giannozzo Pucci – still toil day and night cleaning and repairing works of art, digging out millions of books from the city’s archives, removing mud from cellers. They live in the center of the flood stricken area and they receive no pay. Now, their chief is to help the poor clean up the ruined homes. Money came from everywhere. Americans raised the first million dollars within a week.

Museums and galleries are now open

All of the museums and galleries in the city are now opened with a section of the Uffizi dedicated to the most important damaged treasures. Most of the valuable works of art have been cleaned up and are now again in display. All but a few of the hotels and pensions are back in business with central heating and elevator service and many are better than before. The restaurants are ready; the shops too. Even those on the Ponte Vecchio look just as they had for centuries. The famous doors of Paradise are intact again.

A three-floor exhibit, “Modern Art in Italy”, in the Palazzo Strozzi is drawing thousands of visitors already. Traffic moves freely and the water runs clean. The newly air conditioned opera house, the Teatro Comunale, is ready for summer.

The work goes on – ancient books are been dried out in special ovens, frescoes restored, sculptures cleaned. Many cellers are still filled with mud, some business have never recovered, some families are still homeless, but Florence lives on. A new Rainassance has taken place.