“Έxtraordinary people appear in one’s life only in unexpected circumstances, when mystery and suspense guide one’s chance.”

On the island of Sumbawa, south of Bali in the Indonesian Archipelago, a sultan’s widow lives alone with her memories amid decaying splendor and frayed trappings of a former palace.

She is about 100 years old, with wrinkled face and snow-white hair. Sge spends her days now in regal isolation, residing in the palace built many generations ago in the village of Sumbawa Besar whose inhabitants seem to ignore her presence.

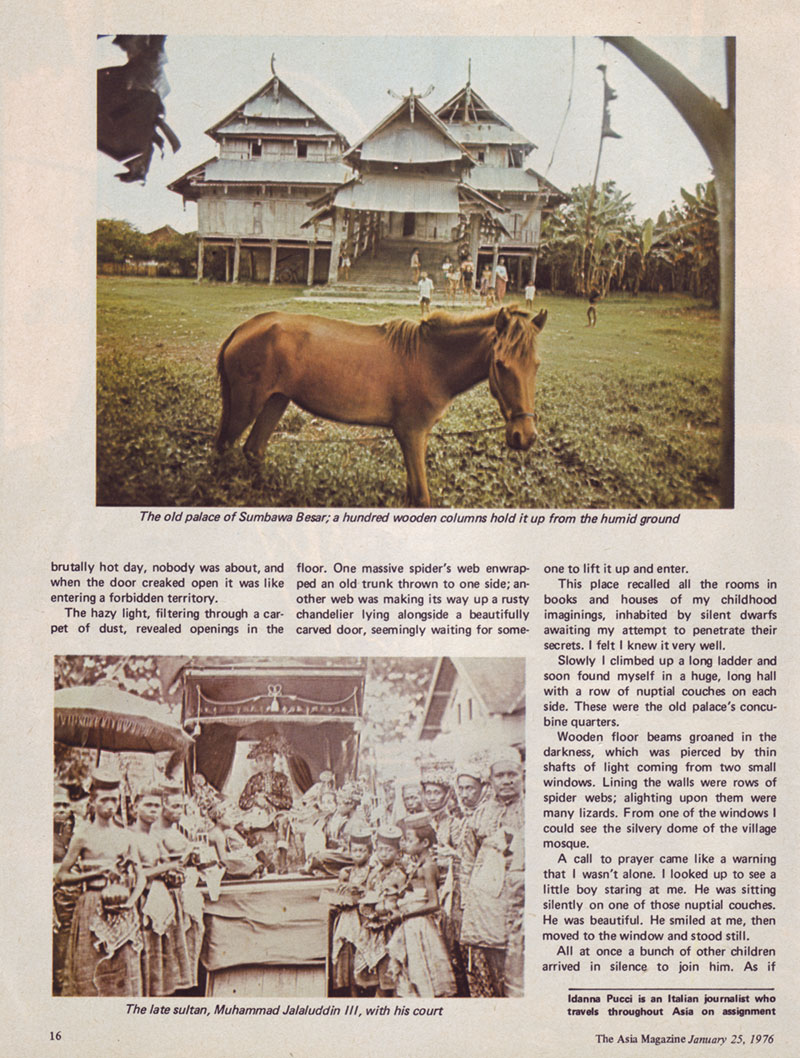

Villagers had told me, in fact, that the old palace was uninhabited. They prefer, it seems, to talk about the “new” palace, built in 1931 by Muhammad Kaharuddin ΙΙΙ, son of the late Sultan Muhammad Jalaluddin ΙΙΙ.

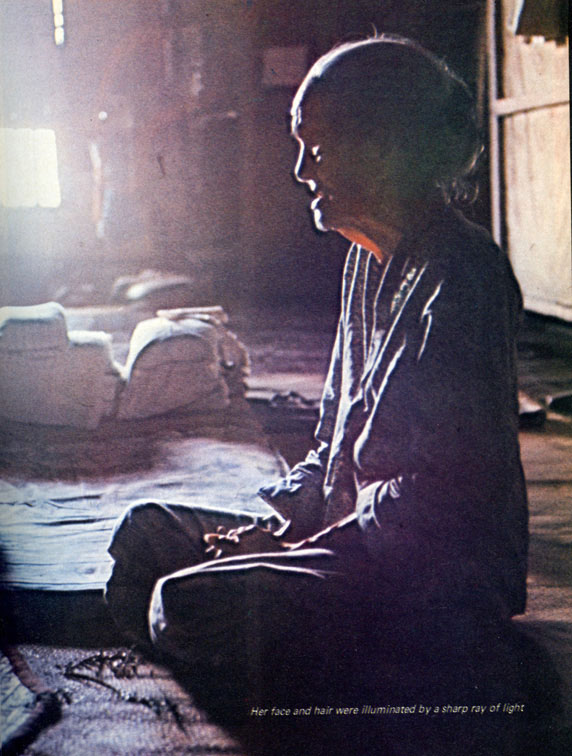

The “new” palace is the villagers’ pride, even if it no longer serves as such; it is a school now. The old palace, meanwhile, is a magnificent edifice made of sturdy lumber, its walls bent under the weight of the past, unaided by restorative injections.

Uninvited, I walked, alone, up a wobbly wooden staircase leading to the entrance door. It was a brutally hot day, nobody was about, and when the door creaked open it was like entering a forbidden territory.

The hazy light, filtering through a carpet of dust, revealed openings in the floor. One massive spider’s web enwrapped an old trunk thrown to one side; another web was making its way up a rusty chandelier lying alongside a beautifully carνed door, seemingly waiting for someone to lift it up and enter.

This place recalled all the rooms in books and houses of my childhood imaginings, inhabited by silent dwarfs awaiting my attempt to penetrate the secrets. enfolding them. Ι felt Ι knew it νery well.

Slowly Ι climbed up a long ladder and soon found myself in a huge, long hall with a row of nuptial couches on each side. These were the old palace’s concubines quarters.

Α call to prayer came like a warning that Ι wasn’t alone. I lookd up to see a little boy was staring at me. He was sitting silently on one of those nuptial couchs. He smiled at me, then moved to the window and stood still.

All at once a bunch of other children children arrived in silence to join him. As if bolstered by their presence, the little boy spoke.

“Come down,” he said in Indonesian, “Follow us.” Downstairs, the enormous center hall seemed filled with life because of children. They dashed and darted about those unsteady floors, plainly indicating that for them the palace was a secret place inherited from the sultan for games and gatherings.

Suddenly the children gathered in front of an open door, pointing and looking at something on the other side, then beckoning me. I came, saw and was stunned.

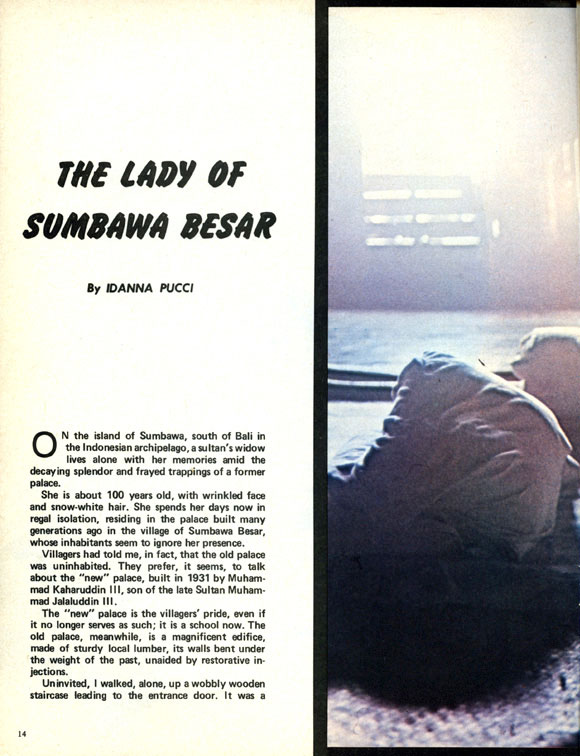

Sitting alone in the center of the dark room was a very old woman. She was illuminated by a single sharp ray of light; her eyes were closed; her face wore an expression of great serenity.

She was sitting cross-legged beside a mattress coνered with what was once fine linen, on which were set hand-embroidered pillows. Α brass bed, draped in an old mosquito net, stood long unused at one end of the room; at the other was a chest with some broken pieces of old Chinese porcelain; what was once a striking red-and-white tapestry hung torn and forlon on a wall.

Ι tiptoed in. The old woman opened her eyes and smiled, extending her hand in an indefinable gesture. Ι bowed my head. The little boy pulled my arm.

“She is the wife of the Sultan…” he whispered.

Then she spoke in the language of Sumbaw, and the little boy translated for me.

“She invites you to sit down.”

Ι sat on the floor and we smiled at each other. She was dressed in white and her small feet were folded into the pleats of her sarong. She looked as feeble as the ray of light entering the solitary window.

She said nothing for a long time. Then something again, seemingly to herself. At that, a little girl came forward with a jug of water. She knelt in front of the old lady and poured some water into a cup.

“She is thirsty,” the boy said.

In this woman’s eyes Ι saw the glittering court moving like the sun around the Sultan, whose power reached the neighboring island of Lombok, where the great volcano Rinjani is located.

Then, slowly and hesitantly, she told me some of her past and the history of Sumbawa. Her solitude and the children’s behavior spoke about her present life; and the future, for her, didn’t exist – it belonged only to the children and myself.

She had seen the palace being built, she said. She had shared the sultan with three other wives and numerous concubines. She herself had been the fourth and last wife. She had lived the last years of a gilded age.

At ne timee Sultan Muhammad Jalaluddin ΙΙΙ had been rich and powerful despite the predominant Dutch control over most of Indonesia. But the island was out of the way, and Sumbawa Besar had been spared the presence of a Dutch representative.

Sumbawa was occupied by Japanese troops during World War ΙΙ. But they only stayed for a short while.

Soon after, in 1949, the old lady heard the news of Indonesia’s declaration of independence and the birth of the republic.

Such matters seemed far removed from her world; but ultimately, they weren’t. Slowly things changed and the old queen witnesses, for the first time after many years of a long history, Indonesians finally deciding among themselves their own future.

She saw little else, but things in Sumbawa Besar had changed irrevocably, too. Soon, her own palace had been turned into a deserted mansion – a monument of the past.

She owns nothing now other but memories and the privilege of continuing to live in a luxury sustained only by her presence. The children take care of her, coming each day with food and water. They clean the room; they wash her sarongs; they help.

She knows little or nothing of the present – of the buses running around Sumbawa, or the radios screaming in the Chinese shops or the mirage of Western life hovering before the eyes of the young.

She doesn’t know that English is taught as the second language in schools; that airplanes land on her island, and that big ships arrive regularly from Bali, Jakarta, and Hong Kong. All she knows is the past.

When I left it was nearly the end of the day. The call to prayer came clearly again from the minaret, but I had the impression that she didn’t hear it anymore.

No matter. She had led a full life, she is warmed by memories and she remains in good hands – who is better equipped to tend the very old than the very young?

I will long remember the lady of Sumbawa Besar.