On February 8th, 1892, the correspondent in Rome of the Florentine daily La Nazione reported that the city’s intellectual and social elite gathered in the Collegio Romano to hear a young man speak. In barely an hour, the orator masterfully painted a detailed portrait of the ancient island cultures whose peoples and customs he had minutely observed at the far end of the world. With simple clarity and eloquence, he spoke straight from the heart, not from any notes. The packed crowd hung on every word, magnetically captivated by his tales of wonder. They watched with rapt attention each of the extraordinary objects he presented, while the magic of his photographs brought the faces of indigenous islanders from South East Asia all the way into that prestigious conference hall.

Queen Margherita of Italy, a patron of the arts and sciences, was sitting at the center of the front row. Fascinated by Elio Modigliani’s descriptions, she did not move until the end. As she applauded, the audience did the same, and the sound of hands clapping exploded in the air with the same loud protracted enthusiasm that happens after a particularly wonderful theatrical experience. Then the Queen spent fifteen long minutes conversing with the inspired naturalist, asking him a myriad of questions. Modigliani, always modest, refrained from highlighting the dangers of his travels, and dwelt instead on the results of his most recent expedition.

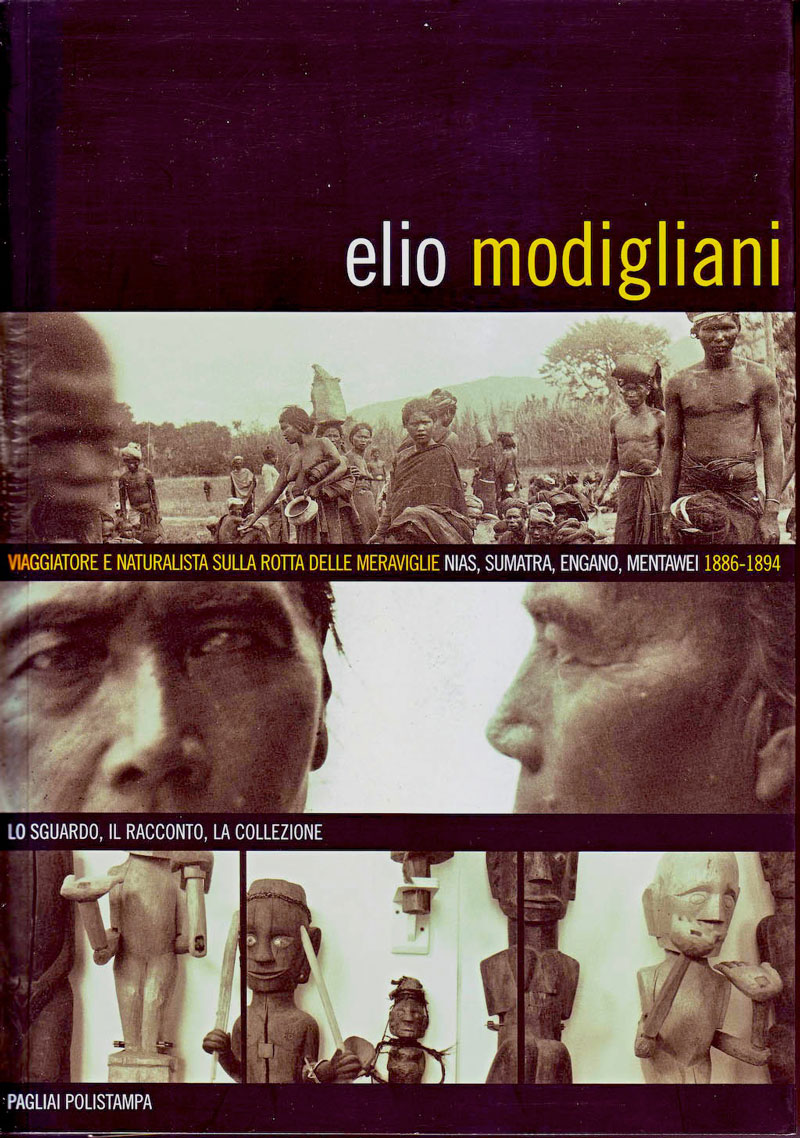

Four years had passed since his first voyage which had taken him to live for six months in the island of Nias, west of north Sumatra, then under Dutch colonial rule like most of the Malay Archipelago. Modigliani was only 26 at the time. But now, he had just returned from his second exploration, fourteen month spent among the Bataks of the Sumatran Lake Toba–known for their cannibalistic practices–and also the people of Enggano, a small island floating further south–mythically inhabited by a population of only women who gave birth only to baby girls, becoming pregnant by eating certain fruits or through the action of the wind. This century-old tale was first reported by the Portuguese fortune seekers of spices who navigated these seas–Alfonso Albuquerque and Magellan’s surviving crew with the Vicenzian scribe Pigafetta. But not a single man before Modigliani had ever really managed to venture into the interior of the island to check from where and why that legend had sprung. The few who had anchored off its shores had sighted naked men–and not women–armed with lances, squatting among the coral reefs. At just 30 years of age, this inspired Italian possessed the experience of a seasoned traveler and was a professional in the fields of ethnography, anthropology, botany, zoology, geography and map-making, photography, first aid medicine, social science and human behavior. He was not an academic, a bookish man, but rather a doer, propelled forward by obsessive curiosity and a taste for wonder. He felt a profound calling to personally confront the facts of distant tribal cultures–systematically collecting whatever could visually represent the peoples’ way of life and beliefs–and transmitting this knowledge to his own contemporaries and future generations. He believed only in what he could experience with his own senses, on location. Nothing seemed ever too impenetrable or difficult for him. Nothing could dissuade his stubborn determination, neither fearful rumors nor local intimidation. In the Italian history of ethnography and anthropology, Modigliani certainly occupies a unique place. But, where did his intrepid path begin? The son of affluent parents, Modigliani was born on June 30, 1860 in Florence, a few months before Italy became a unified nation under the royal House of Savoy, and the very city was chosen as capital. At first glance, nothing could be more distant and alien to Florence than the jungles of Sumatra or the remote islands off its coast. Nevertheless, as was the case with the humanists of the Renaissance, Modigliani too perhaps was not satisfied with a provincial image of man. By going back in time and delving into ancient uncharted animistic societies, he embarked on a pilgrimage to the sources of civilization, a dream he had nurtured since childhood. In 1883, he graduated in law from the University of Pisa only to please his parents. But he never became a lawyer. Instead, he followed his true passion, the study of natural sciences and anthropology. Three years earlier, during a summer holiday with his family in Liguria, he had excavated a cave unveiling an unknown Neolithic burial ground, a treasure of great anthropological significance. This event marked the beginning of his true path, paving his way alongside his Tuscan spiritual ancestor-travelers and discoverers of new worlds. Modigliani, like the Florentine Giovanni da Empoli and even Amerigo Vespucci, looked beyond visible horizons. He wrote extensively, and always in the first person. His engaging style transmits the suspense of his daily quest, the difficulties and setbacks that constantly lurked like benevolent or, more often, malevolent ghosts along the way. And though his books have never been translated from Italian, they remain among the most fascinating and informative accounts of nineteenth-century explorations in the Dutch East Indies–now the Republic of Indonesia. His Viaggio a Nias—Journey to Nias–is a landmark testimony of the only living Neolithic culture on earth. Modigliani must have known a lot about Nias before leaving for his first hazardous journey. He spent an extensive period of research in the archives of the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam, after which he became even more determined to record first hand the habits and customs of a people believed to descend directly from the original settlers who had migrated south from Asia’s highlands 2,500 years before. Brave warriors, they had brought with them the knowledge of rice cultivation, and the craft of pottery and bark cloth. They bred pigs and cattle for religious sacrifices. Their huge wooden houses were a marvel of architecture. Stone was the building block of their vast outdoor communal assembly spaces, their monumental memorials to the dead, and the narrow staircases leading all the way up to villages set high like fortresses in strategic places. Their art was sculptural and mostly concerned with life after death. Nowhere else in the world had the role of megaliths in a society been so pronounced as in Nias. It is no coincidence that Modigliani chose to sail there. Throughout his writings, his dislike for seafaring is evident. There was no remedy from the affliction of seasickness, his constant travel companion. And yet his passion for far flung explorations automatically implied crossing great expanses of water, from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, and finally the Indian Ocean all the way to the shores of Sumatra. And from there, more difficult sea adventures awaited him in order to reach first Nias–and later on Enggano and the Mentawei Islands. Vessels were at the mercy of unpredictable currents, sudden banks, and coral reefs which made sailing extremely dangerous, and landing often impossible. Over the centuries, these natural elements had greatly contributed to isolating these islands from the rest of the Malay archipelago, preserving in a sense their inhabitants’ way of life, for the better or the worse. Without losing sight of his purpose and dream, Modigliani fought seasickness and fierce waves, but always ended up by finding a natural harbor in the midst of hopelessness. Of course, he was never alone during these precarious crossings: with him were the men he had hired to help him collect, gather, and carry his precious cargoes of objects and insects. And then there was also always the difficult task of how to gain the islanders’ trust. Modigliani was virtually the captain of a fully equipped ambulant scientific laboratory–complete with a photography studio and darkroom, and all the necessary accouterments of his trade–all of which, had never been seen before by his indigenous hosts, and provoked suspicion, even fear. The news of that small industrious workshop spread even as far as the domains of the Bataks in north Sumatra. This fierce and proud people of Himalayan ancestry inhabited the highlands around Toba, the largest lake of South East Asia, born from a prehistoric volcanic eruption, one of the deepest lakes on earth. Modigliani’s particular daring and independent spirit never allowed him to take “no” for an answer. He defied the order of the Dutch colonial authorities who had categorically forbidden him to venture into Batak territory with which they were at war. Had he been less self-confident and courageous, he would not have discovered the great Sapuran Si Arimo Waterfall, magnificently exploding with gushing volumes of water from Lake Toba. And then there was the dreaded malaria to reckon with. Wherever he set up camp, his descriptions give you the impression that he and his men were attacked by mosquitoes from all sides, with no defense possible, other than gulping down large quantities of quinine which, thank God, never seemed to run out. One almost can hear the constant buzz of the dreaded creatures, their stings eager to strike at all times of the day or night. One imagines this young Florentine weaving his way through the dense tropical vegetation with a line of porters carrying great weights of wonders on their shoulders, including kilos of miraculous quinine–a medicine which not only fought back the poisonous disease, but also helped create this traveler’s benevolent reputation as a magician who could save lives. Modigliani never really seemed to think about himself or the risks involved. Like so many young people, he felt perfectly confident and vigorous, able to overcome all and everything. In the face of controversy, he reinvented himself and dealt with imaginative solutions, like an artist of the moment, knowing that no mistake was possible, and that survival hinged on the right decision. He was young, but wise. Perhaps because he came from a wealthy family–and personally financed all his expeditions–he was not really impressed by riches, but drawn only to collecting objects that could contribute to a better understanding of bygone ages. His obsession with recording for posterity led him to aggressively persuade people to pose in front of his camera by falsely claiming its healing powers, and one night even to defile a graveyard and remove human skulls. But his final purpose was only educational. He was not a predator or an exploiter, and had great regard for the people he encountered. He lived in an age of colonialism, when even his own country of Italy was starting to turn its gaze towards North Africa with colonial ambition. Yet, he did not seem to belong to his own time, and was very critical of the Dutch exploitation: he saw it as a great threat for the future of the indigenous populations he had come to know. And so he kept apart, and functioned independently. Modigliani must have liked his own company. For months on end, while living in those faraway islands, he had no one to talk to in his own language and certainly no one with whom he could exchange ideas and findings. Yet he never seemed to be homesick. On the contrary, he departed from Western civilization with a great sigh of relief. He could not wait to breathe the air of primordial virgin territories filled with unknown species of flora and fauna, and human beings at ease with the invisible world. He was fascinated by their languages, oral tradition, and modes of communication, spending hours jotting down local words. In the poetic style of four verses with alternating rhyme as well as the cadence of the courting songs of Nias– among the most beautiful in the literary heritage of the archipelago–Modigliani perceived similarities with the familiar folk songs of his rural Tuscany, improvised by the farmers sitting under the stars in cool summer nights after a hot day’s work, harvesting wheat. He recorded many patun poems down on paper, carefully translating them, melody and all. In October 1886, Modigliani left Nias never to return. His last journey, in 1893, took him south to Sipora, one of the smallest islands of the Mentawei Archipelago, where animism survived intact. Everything that the Mentaweians could visualize as an entity possessed a soul: all living creatures, and even objects and natural phenomena like floods and rainbows. Nothing could be used without considering its specific psychic disposition. Each thing only consented to letting itself be used. The people of Mentawei, ecologists par excellence, lived at service of nature. They had understood their place in the universe and how each life was a crucial part of a whole system. But, in Sipora, Modigliani fell gravely sick. Struck by wild relentless fevers, he was forced to return to Italy. After this last fateful trip, he was never again physically able to venture forth on any further explorations, so far away from Florence. So he delved into his notes and memories, writing his books. He donated his archive of landmark photographs and his cargoes of tribal wonders to the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Florence to honor his mentor, Paolo Mantegazza, the Italian father of Anthropology. His zoological collection, he gave to the Museum of Natural History of Genova. In time, he became a distinguished personality and continued to lecture with passion to rapt audiences. The Italian Geographical Society awarded him the Gold Medal for his scientific contributions. Even the Netherlands recognized his outstanding endeavors and awarded him the order of Orange Nassau, forgiving him for having defied Dutch authority back in the days of his expedition into Batak territory. Now, barely a hundred years have passed, and the ancient island cultures of Modigliani’s youth–which had survived undisturbed for so many centuries– have shattered into pieces of a puzzle never to be put back together again. At the onset of the new Millennium, a massive earthquake found its epicenter in Enggano, bringing havoc and death. Most houses were destroyed, crushing many of the two thousand inhabitants in their sleep. The few who survived fled the island by boat. The initial tremor measured 7.9 on the Richer scale, and it was followed by 400 aftershocks that sent ripples of waves north as far as the Mentawei islands, whose ancient practice of tattooing as a sign of bonding had provoked the infection that almost killed Modigliani and forced him to give up his far flung travels. And what happened to his most beloved island? In barely one generation, Nias was shaken awake and wrenched headlong into the modern world. The global economy–in a story of greed, riches and despair–irreparably crippled this unique megalithic world treasure. In a classic “boom and bust” cycle, a monoculture dependency was created over the last few years. Seeds were sown for ecological disaster. In the early 1970, the patchouli plant–an aromatic minty shrub, whose distilled oil offers the dual use of perfume and healing ointment for wounds–was first introduced to Nias by an elementary school-teacher named Laseto who planted it innocently on his plot of land. Ten years later, patchouli had become the main export with its price rising by the day. The deep forests that had blanketed the island, and circled the indigenous villages for centuries, punctuating fields of rice and sweet potatoes, were suddenly chopped down. Across Nias, patchouli plantations sprouted excitedly. Magnificent ancient trees turned into fires to distill the precious oil. It all happened quickly, no land regulation existed. The appetite of distant merchants in Sumatra and Java grew as pharmaceutical markets in Europe and America demanded more patchouli. At one point, seventy per cent of the people of Nias were engaged in the industry. Staple foods had to be imported for the first time in the island’s history. Globalization, the heady ambition of Suharto’s regime, was eagerly transforming traditional self-sufficient societies across Indonesia. In the Spring of 1998, massive student protests in the capital Jakarta forced Suharto to step down. The Asia monetary crisis had turned riches to despair. Entire fortunes were lost, even in Nias. The price of patchouli stumbled. Small farmers were reduced to poverty. And, now, tragically, there is little hope for their forests to grow back. Patchouli is a plant that kills humus in soil: it takes at least seven years for other plants to take root where it once grew. And then, in August 2001, the wild whims of nature struck Nias. A new kind of wet monsoon came with violent rains pouring down for days and nights. Apocalyptic floods and landslides lashed across the landscape. Gushing walls of water roared down mountain-sides. Entire clusters of houses were swept away. Hundreds died. Thousands became homeless. It was a calamitous natural disaster, the likes of which had rarely been seen before. Immediately, ecologists blamed the catastrophe on the irresponsible destruction of the forests by the patchouli plantations. Nature’s bounty had been irrevocably scarred in less than thirty years, and there was no going back. Today, Nias’ legacy to the world is modern third-world poverty and a transfigured society shockingly divorced from its past. Modigliani’s hunger to document, photograph, archive, collect, and preserve Nias’ unique stone-age culture now takes on powerful meaning. Like the tragic vanished life of Native Americans, never again will we be able to look at the world of Nias as vibrant, self-assured and complete. Its entire universe has been ravaged, its heavens have cracked, the Gods have fallen. Only through Modigliani’s eye, can we ourselves see that world lost forever. Only through his lens can we wander into boisterous villages, where today only the monumental megaliths remain intact. Only through his words can we hear ancestors’ voices and listen to the sacred stones which speak beyond the spiritual desolation of our age. Perhaps, this represents Modigliani’s greatest gift to humanity. Braving the elements, he persistently gathered symbols, relics, poetry, and images in order perhaps to bring us face to face with the timeless soul of our family of man, forever. When Elio Modigliani died on August 6, 1932, at the age of seventy-two, his only daughter, Mohua, was ten years old. Her name means “perfumed” in the language of Nias, a term used only in sweet exchanges of love.

If I die before you, please come

Kalau tuan jalan dulu

To my grave with a frangipani flower.

Jariken daku daun kamboja

If you die before me, wait for me

Kalau tuan mati dulu

In Heaven but remember to stand at the door.

Nantiken daku di puntu sorga

From where come the leeches?

Darimana datang lintanya

From the ricefields they descend to the river.

Dari sawa turun di kali

From where comes love?

Darimana datang cintanya

From the eyes it descends to the heart.

Dari mata turun di hati