When Idanna Pucci undertook the daunting mission of building a house in remote Bali, she quickly realized that she was more than a stranger in a foreign land. “While the rule in one village is often the exception in the next,” she says, “no one tells you what to do. It is up to you to discover and enter into Balinese social law.” Indeed, no one told Pucci and her husband, Terence Ward, what to do when they learned that their land lacked natural spring water. “It was a miracle that the centenarian village priest, who prayed under the full moon in the temple above our land, was rewarded with a sign – now are aqueduct provides water for us and 60 families. People say the Gods have blessed us.”

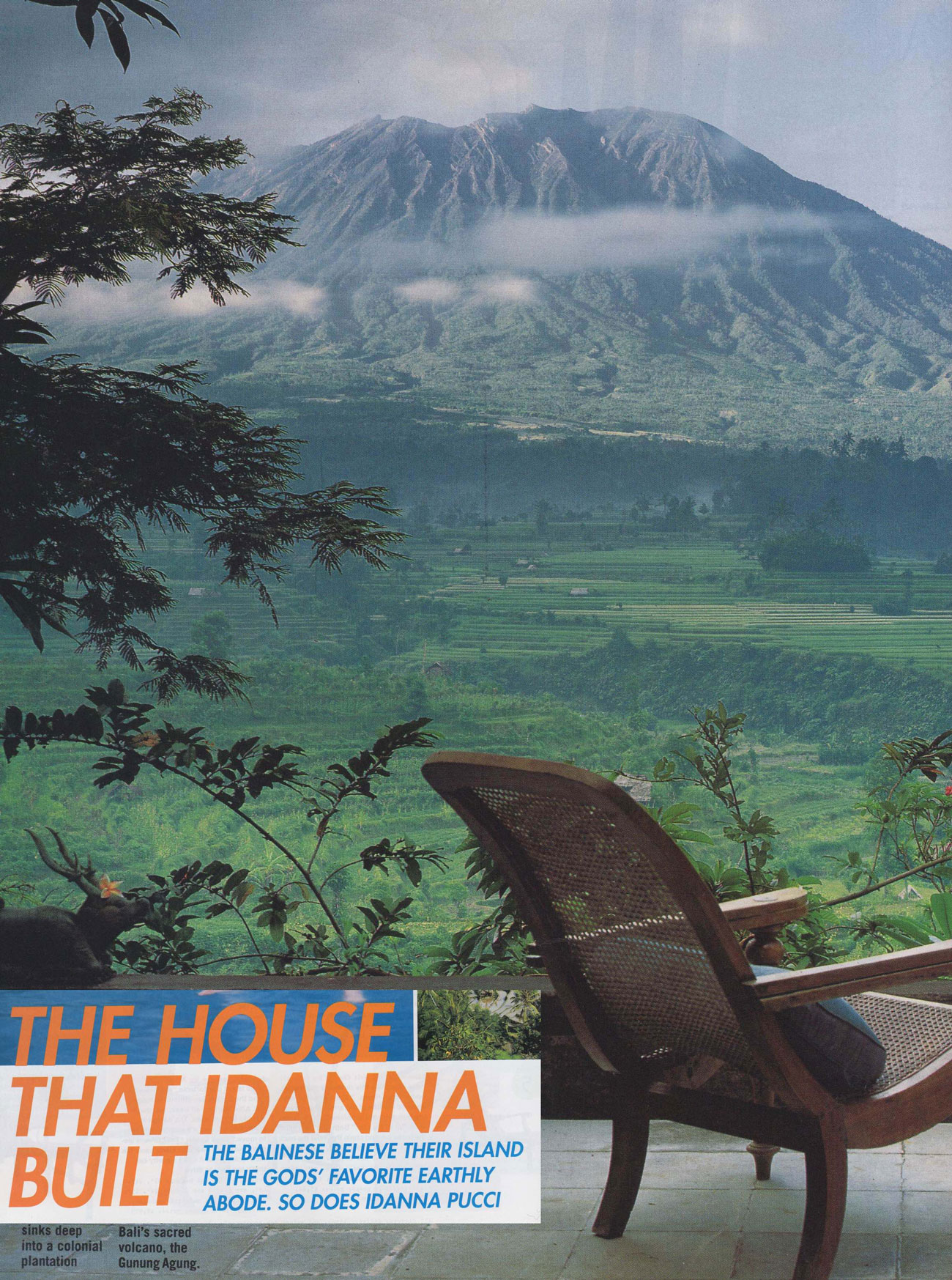

They certainly have blessed Bali, whose people traditionally consider the verdant island the gods’ favorite earthly abode. An oasis of predominantly Hindu culture (95 percent) within the otherwise Muslim Indonesia, Bali is teeming with tens of thousands of carved lava stone temples and altars to one or more deity. These shrines, which always seem to be invisibly replenished with black-and-white-checked cloths and lavish offerings of fruit and flowers, are permanent reminders that the world is caught up in a perpetual balancing act between good and evil.

Bali’s strange allure captivated Pucci 25 years ago, when she made her first visit to the island, and has lived there sporadically ever since. “Life in Bali is governed by unwritten religious karma,” she says. “Our land and life came to us in the form of an idyllic seduction, rather than a compulsive endeavor.” A serenely beautiful woman and passionate storyteller whose book, The Trials of Maria Barbella, was published this spring by Four Walls and Eight Windows in New York, Pucci has made her long-standing dream of building a simple house in Bali come true: today, she and Ward divide their time between Via dei Pucci in Florence (she’s the niece of the late Italian fashion potentate, Emilio Pucci); the National Arts Club on New York’s Gramercy Park; and Bali’s Sidemen region, which lies eight miles inland from the ancient royal capital of Klungung.

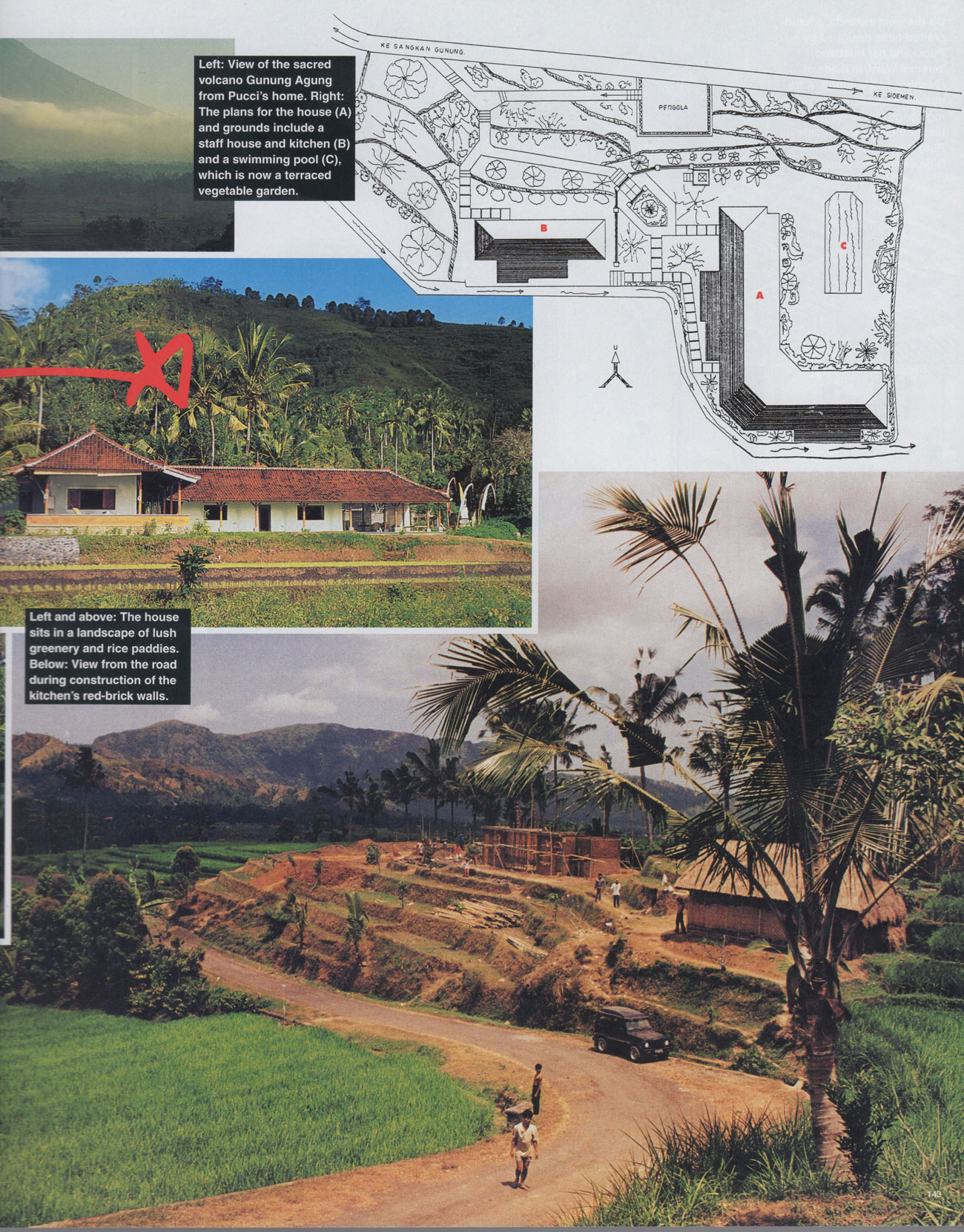

A ceremonial blessing was arranged with the local hereditary ruler, Tjokorde Gedé Danging, for the groundbreaking. They prayed to the rice goddess Dewi Sri, and a compulsory bamboo shrine was erected facing the sacred volcano Gunung Agung (king of the mountains) to endure the workers’ safety. A crew of a dozen Javanese was aided by as many as 60 villagers who helped terrace the surrounding land. (Bali’s rainy season between December and May is followed by unmitigated sun, so water must be carefully rationed through a complex system of dams that channel its flow.) Other considerations centered on local custom: every private house must also have its own temple, its inhabitants must sleep with their heads facing north or east (i.e. in the direction of Gunung Agung), and sacred books are stored in a lofty place (the realm of the gods).

The post-and-veranda construction, which looks as if it has been built for a prosperous Balinese family rather than foreigners, was completed in seven months. An expansive linear open-air pavilion surrounded by clove trees, bougainvillea, gardenia, and frangipani hugs the terrace promontory. Two opposing wings are set at right angles and meet in a common living area. The simple plan is an L-shape that completely defers to the breathtaking landscape and majestic views.

A stone walk connects a separate kitchen (and housing for staff) to the main residence. In the spirit of communal living, staff members are allowed to cultivate the land and sell its yield. “The initial thought to put a swimming pool in the protected courtyard where vegetables now grow was a sacrilege, “ Pucci says, with an omniscient smile.

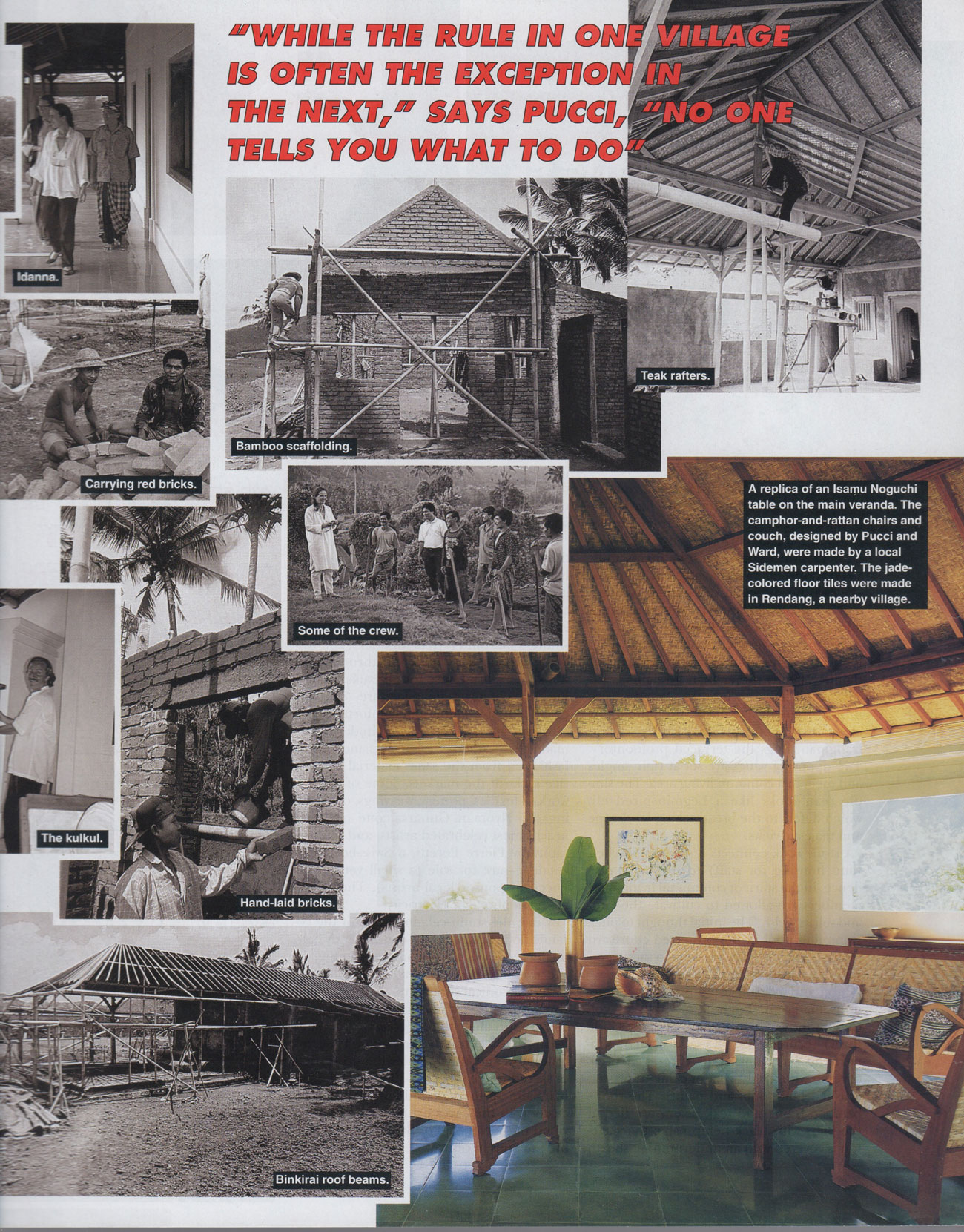

Pucci and Ward insisted on using indigenous materials. Foundation walls of volcanic stone (carried from nearby Unda River) secured with lava-sand cement support the bata merah (fired red brick covered with a light coat of cement, plaster, crushed lime stone, and paint). The roof’s bamboo frame and teak beams are tired at the joints with black hemp rope; the skeleton is covered with an underpinning sheath of bedeg, (woven bamboo sheets) and exterior terra-cotta tiles. Temporary bamboo scaffolding was used to raise it.

The hands-on craftsmanship eliminated the need for nails and glass. Twenty-seven hand carved teak pillars are supported on lava-stone basis, the doors have been intricately carved from teak (and have typically low lintels), geometrical cross-weave teak shutters slide and retreat on tracks, and vertical bamboo slats screen bathroom windows. “This is a house fro all walks of life,” Pucci says of its pragmatic nature, “so it was essential to live simply and comfortably.”

Rooms are scarcely furnished: locally made chairs and desks, curtains and pillows fashioned from the same material used in rice sacks in the markets. Some of the art-works are textiles, pottery, weavings, and photography by Pierre Poretti, a Swiss-born Bali resident. They don’t use a telephone or electricity.

By day, the sunlit celadon glaze of the ceramic floor tiles reflects a cotton candy halo of fleecy clouds above Gunung Agung. In the evening, deep beneath the volcano towering conical silhouette, the syncopated rhythm local traditional anklung orchestra (drums, flutes, gongs) resonates mysteriously through the valley. Its seems that Pucci and Ward under the protection of a sacred tree bark and a 300-year old mask of a Balinese Goddess (hidden, according to custom in the eaves of the roofs), have divined the secret soul of Bali and are thanking the gods in return.