In the region of Tana Toraja, a primitive and hauntingly beautiful place on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia, buffaloes must never be left alone.

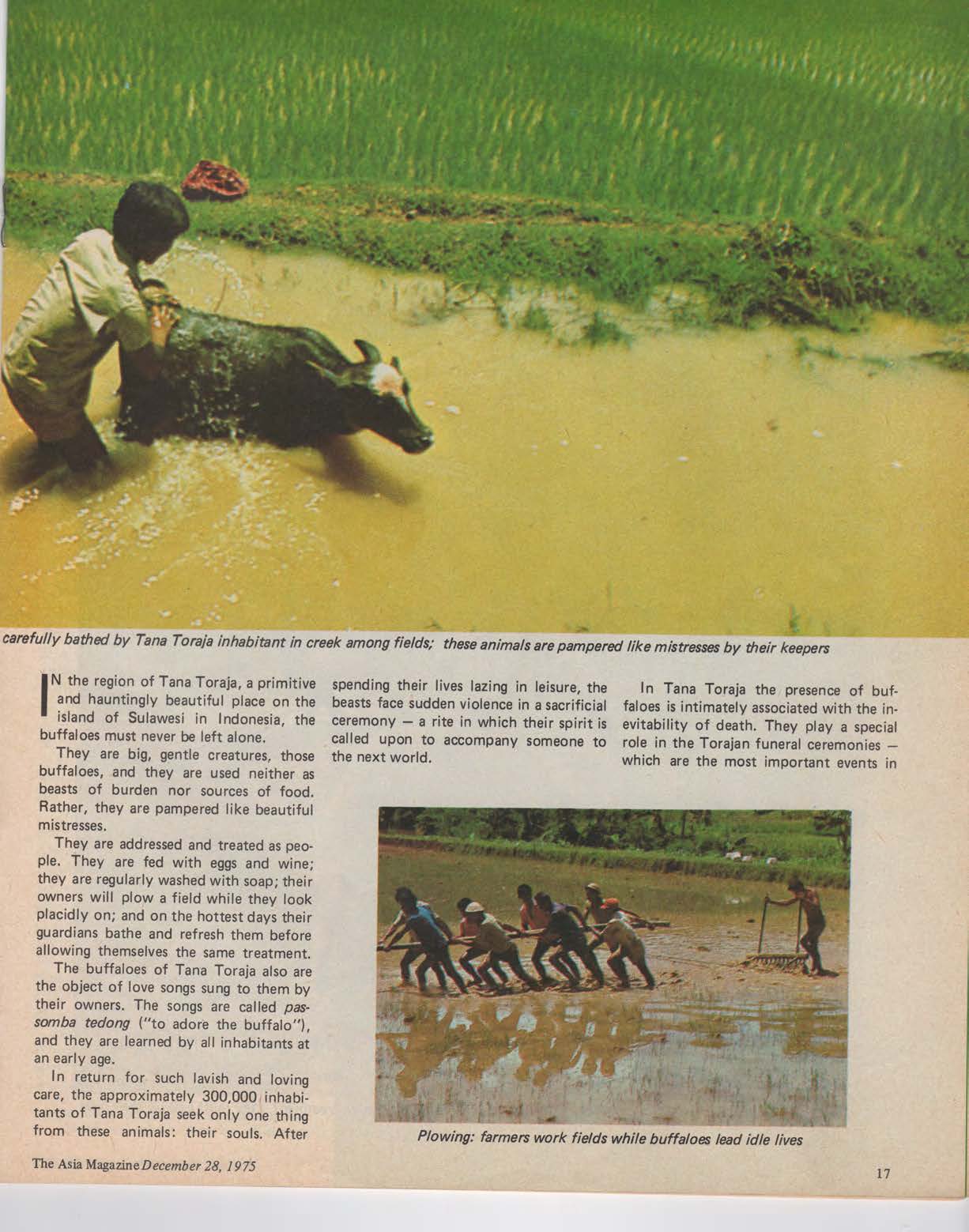

They are big, gentle creatures, those buffaloes, and they are used neither as beasts of burden nor sources of food. Rather, they are pampered like beautiful mistresses.

They are addressed and treated as people. They are fed eggs and wine; they are regularly washed with soap; their owners will plow the field while they look placidly on; and on the hottest days their guardians bathe and refresh them before allowing themselves the same treatment.

The buffaloes of Tana Toraja also are objects of love songs sung to them by their owners. The songs are called passomba tedong (adoring the buffalo) and people learn them at an early age.

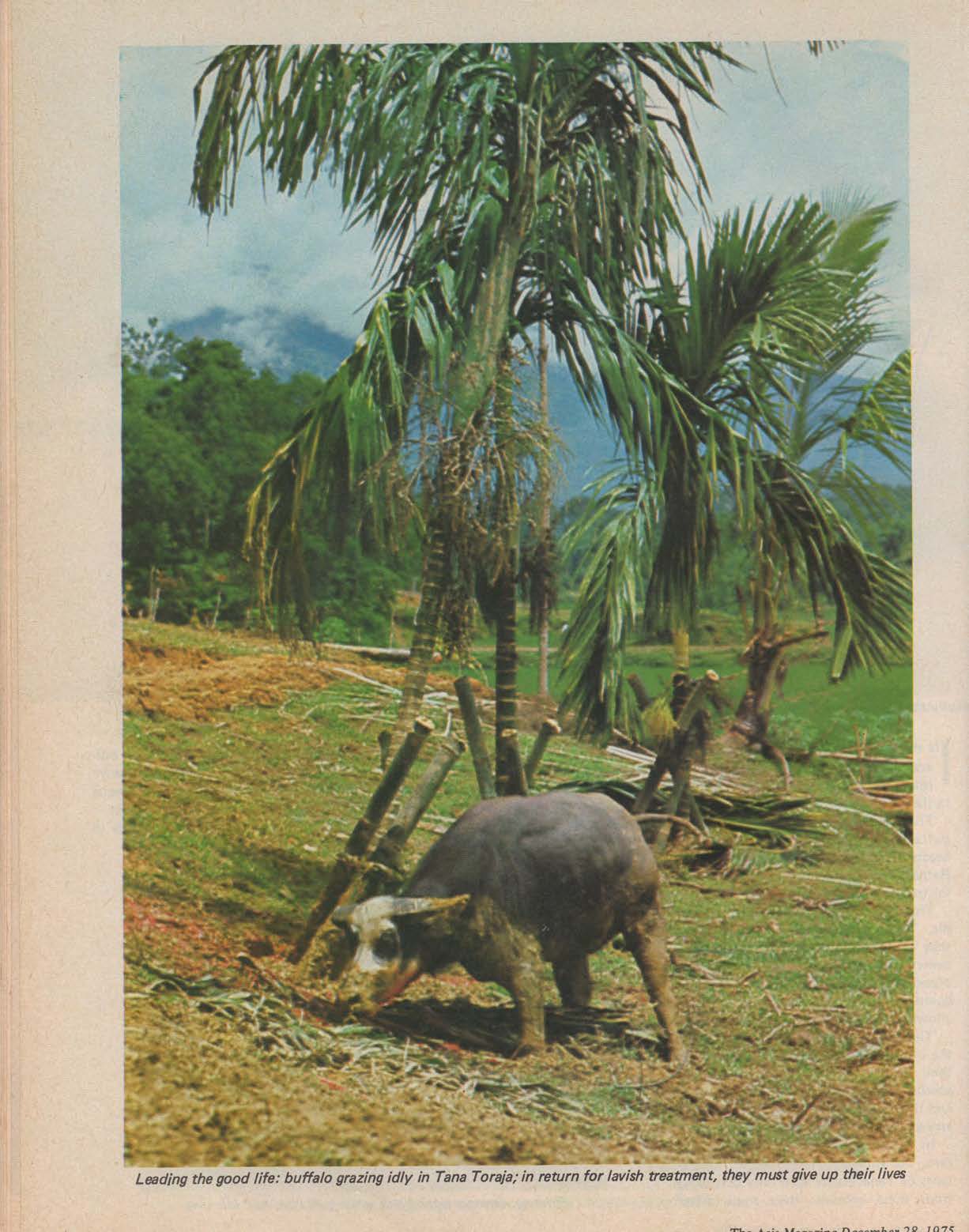

In return for such lavish and loving care, the approximately 300,000 inhabitants of Tana Toraja seek only one thing from these animals: their souls. After spending their lives lazing in leisure, the beasts face sudden violence in a sacrificial ceremony – a rite in which their spirit is called upon to accompany someone to the next world.

In Tana Toraja the presence of buffaloes is intimately associated with the inevitability of death. They play a special role in the Torajan funeral ceremonies, which are the most important events in the lives of the people.

Tana Toraja inhabitants believe that the spirit of the deceased will need wealth in Puya, the land of the souls, in direct proportion to the amount of wealth enjoyed in life. The buffaloes are a symbol of that wealth, and thus must accompany their owner to the land beyond.

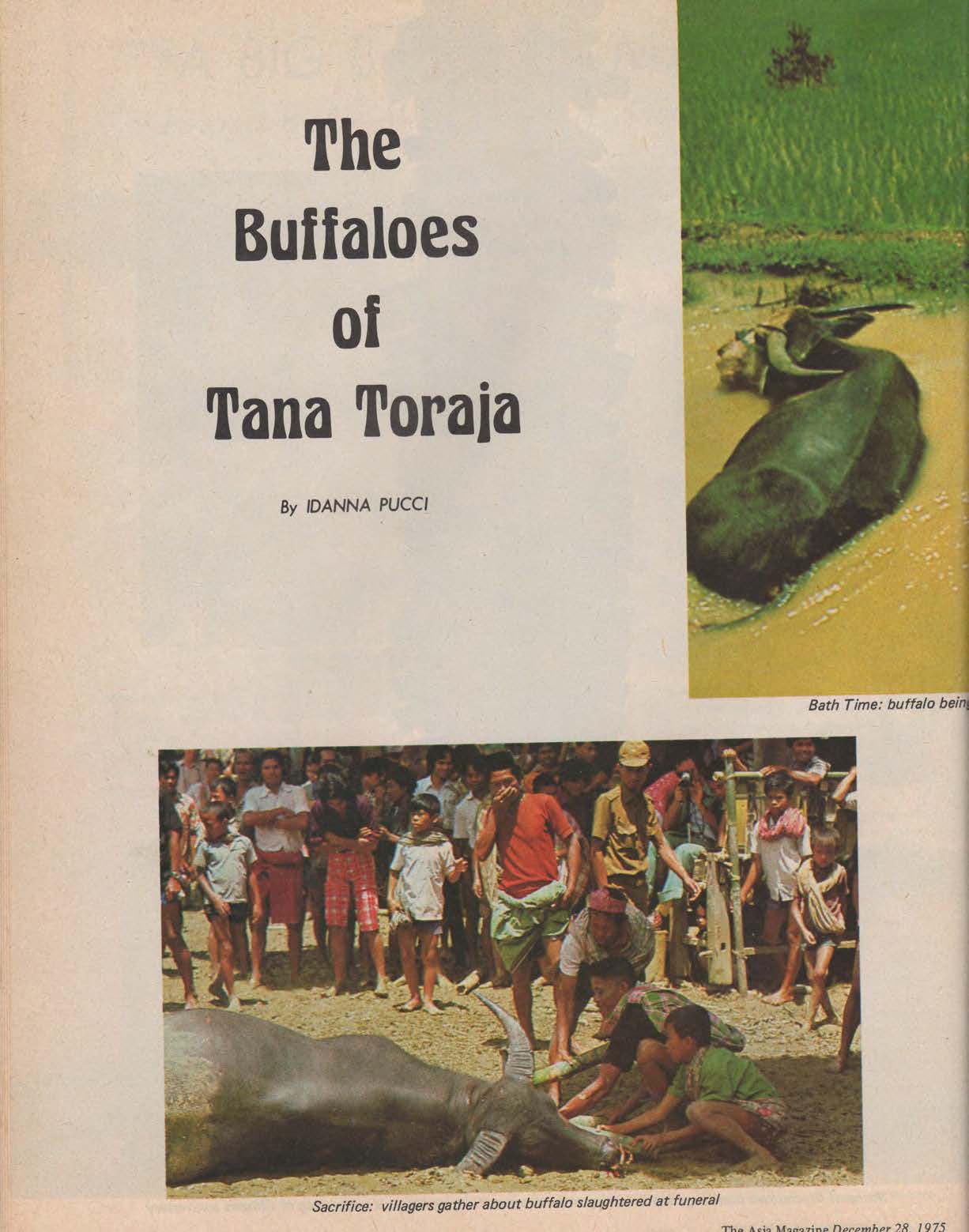

The buffalo sacrifice highlights a funeral. It takes place in the Rante, a special site marked by enormous stones, each of which marks a generation of the deceased person’s family.

During the funeral period, which often consumes several days, the sacrificial buffaloes are tied to these stones. It is not a random thing: each animal has its own particular waiting place, depending upon its beauty and status.

Rules and traditions are strictly followed in this matter, and mistakes are intolerable. Shame will fall for years upon the family whose buffaloes are not properly placed.

The sacrificial victims, moreover, are not only those owned by the deceased. Relatives and friends attending the funeral are expected to contribute their own animals to the sacrificial ranks.

In fact, relatives’ generosity will directly affect the size of their inheritance, while friends’ offerings will enhance their status within the community.

Similarly, the deceased person’s community standing is measured by the number of buffaloes sacrificed at his funeral.

The funeral of a poor person can end n one day, with only one buffalo being offered. In the case of a rich or highly regarded person, however, a whole week sometimes is required to the slaughter of several hundred animals.

Among these animals might be several spotted buffaloes, called sakelo or bongsa by local inhabitants. These are a special breed and their price can go as high as US$2,500 – more than 10 times the price of an ordinary buffalo.

However unhappy the prospect of dying, being accompanied by such treasured specimens offers much solace to the people of Toraja.

On the day the huge stones reach the village, at least seventeen buffaloes must be sacrificed in the Sambuang Batu rite. During the funeral days, the buffaloes are tied to these atones to wait for death. They may also be tied to the trunks of areca, sugar palms, or to a special Torajan pine tree, in this case called Sambuang Pattung wich is a hard bamboo. Every buffalo has its own place depending on its beauty and royalty. Rules and traditions are strictly followed. Mistakes are not accepted. Shame will fall for years on the family whose member makes a mistake.

The traditional law of inheritance, still in force today, prescribes that the deceased’s properties must be divided among the heirs in proportion to the value of the animals, especially buffaloes,each has contributed to the funeral.

Any heir who fails to meet the obligation will have to be satisfied with Ba’gi, a small portion of the properties receives before the owner passes away. The death ritual also serves as an inheritance tax: the spirit of the slaughtered animals accompany the deceased to the hereafter, and meat of the onimals is offered to all the villagers.

On the first day, the day of welcoming when the guests arrive by the hundreds bringing the buffaloes as gifts, four animals are slaughtered. They are killed in a unique way called ditinggoro – a single stroke of the la’bo (sword or long knife) at the neck. The blow is dealt only by specially trained men.

The following days are dedicated to the supreme ritual of the Rapasa Doan, and the remaining animals are slaughtered.

When the deceased is poor, the funeral ends in one day because only one buffalo is killed. Three buffaloes result in a ritual of three days and three nights. The whole week is needed for the funeral of a rich or noble person. In this case not less than twenty-four buffaloes are slaughtered and sometimes up to two hundred.

After the buffalo receives the death stroke, it start swaying and moving in a slow motion dance. Then it .falls. The blood flows from its throat as from a fountain, and people, mostly children, run from all side to fill their bamboo tubes with the sacrificial blood.

Later, the meat of the buffaloes and pigs is cooked after being pressed into bamboo tubes, and adding the blood, the ultimate delicacy. Then the tubes are cooked over the fire and the blood becomes a tasty gravy.

Some children roll over the body of the dead buffalo, playing and caressing its head, half severed from the body. The animals are then cut into pieces. The skins will be sent to Ujung Pandang, because people in Toraja never work the buffalo skin. The meat will then be laid out on the pantenuan, a specially built platform near the rante, from where it will be distributed. The Chief of Tradition closely watches that the right piece is given to the right person. Noblemen receive different pieces from the ones given to the people belonging to the middle or low class. If a mistake takes place, the Chief of Tradition may be killed, the offence is so great.

The beautifully decorated Toraja houses frame all ritual of life and death. Buffalo horns adorn the front of some houses, especially the ones called tongkonan or clan houses. One can find out the number of funerals which have already taken place in a village by counting these rows of buffalo horns. A buffalo’s cup in front of the clan-house marks the greatness and aristocracy of the family.

Buffaloes in Toraja spend their life lazing in leisure. Violence come upon them suddenly when their spirit is called upon to accompany the soul of someone to the spirit world. People do not demand work of these beasts, but their souls.

During their protected lives, songs are sung to them. Songs of love and adoration. Songs called Passomba Tedong (“Adoring the buffalo”) which sound like serenades. Tunes and words which people learn to hum at an early age, an age when they also learn that those, huge, fat, harmless animals must never be left alone. Even their violent death will be witnessed and appreciated by hundreds of people sipping tuak.