Whenever I return to Bali, I make my pilgrimage to the royal court of justice in Klungkung, before heading towards the sacred volcano. It was here, for me, that it all began. This forgotten town, once the royal capital, is the gateway into the province of Karangasem that lies far from the tourist invasion to the south. Worlds apart. Terraced ricefields, cool winds, thundering rivers, lush forested hills, all under the shadow of the towering volcano. But this land holds much more than meets the eye. It is a holy region. It is here, under the island’s most sacred volcano, the Gunung Agung, (King of Mountains), that the secret soul of Bali still thrives.

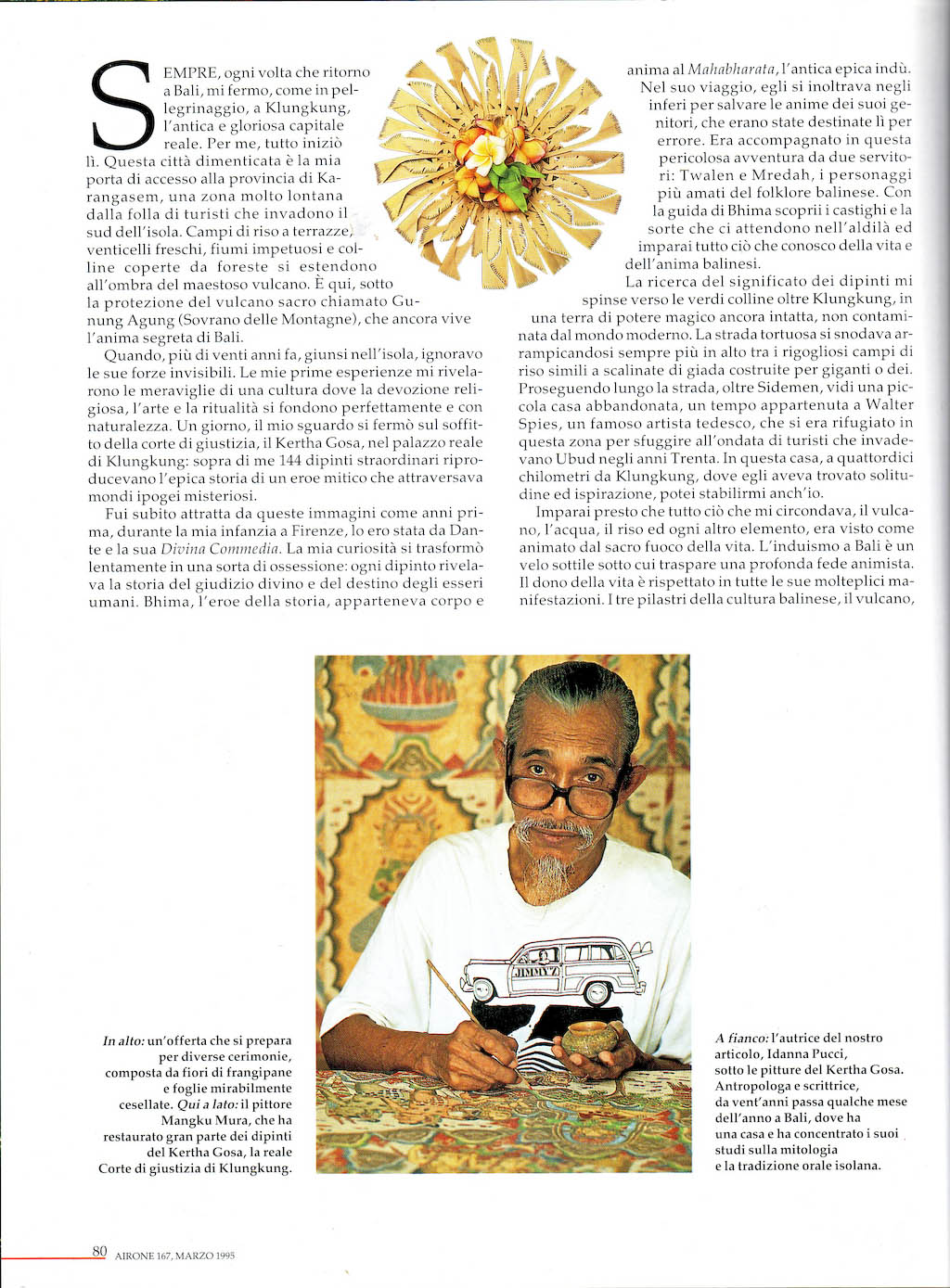

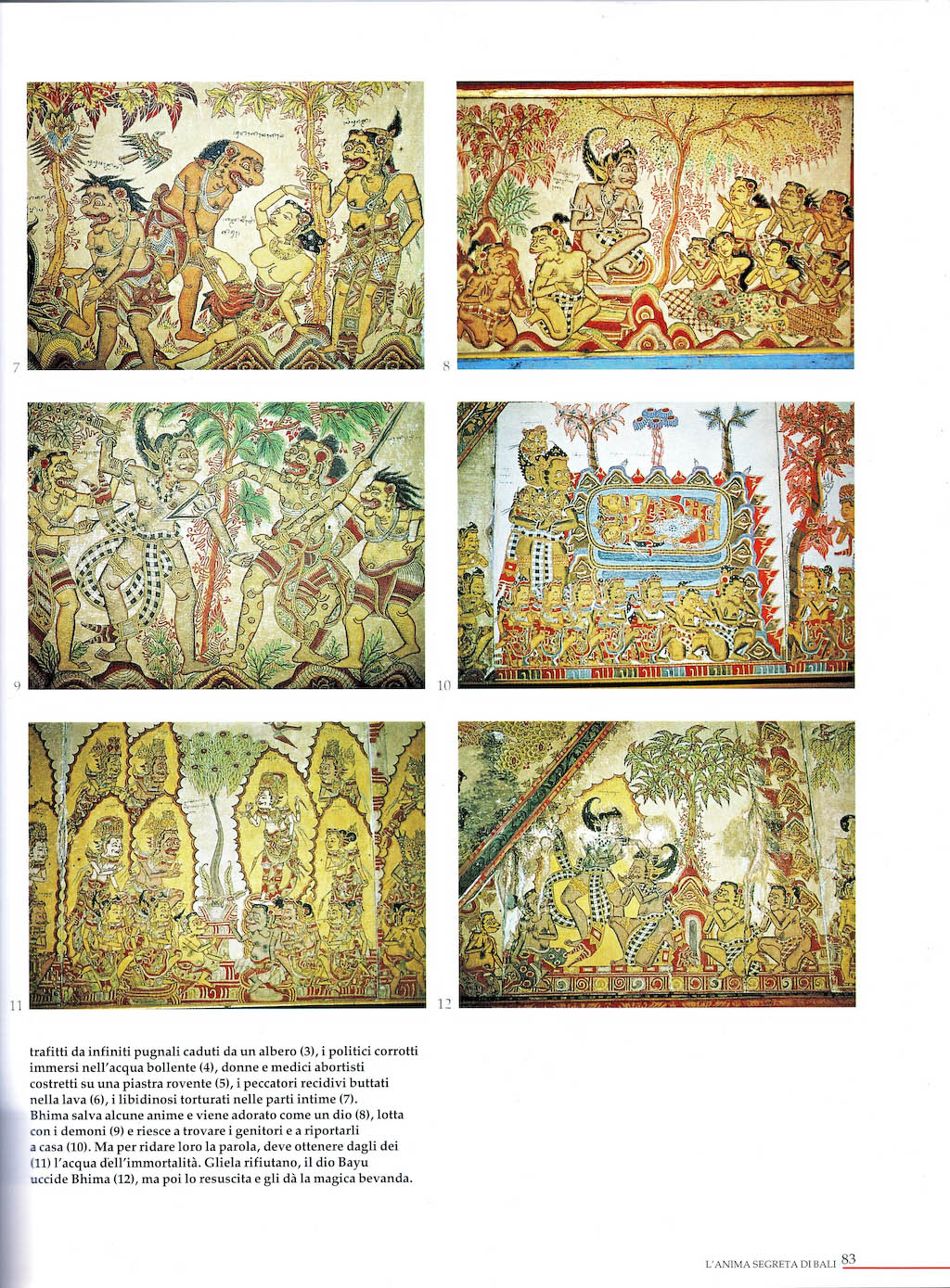

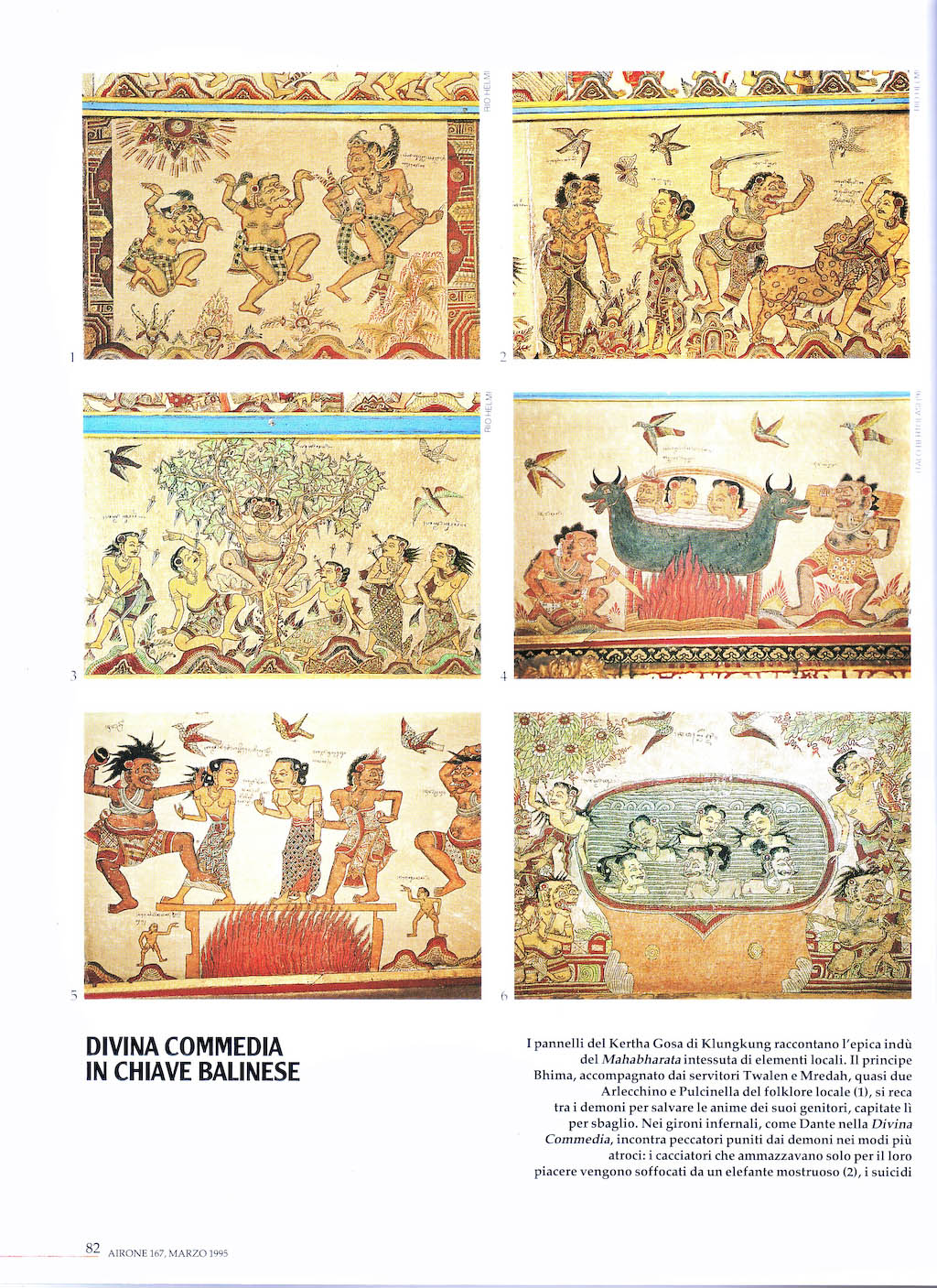

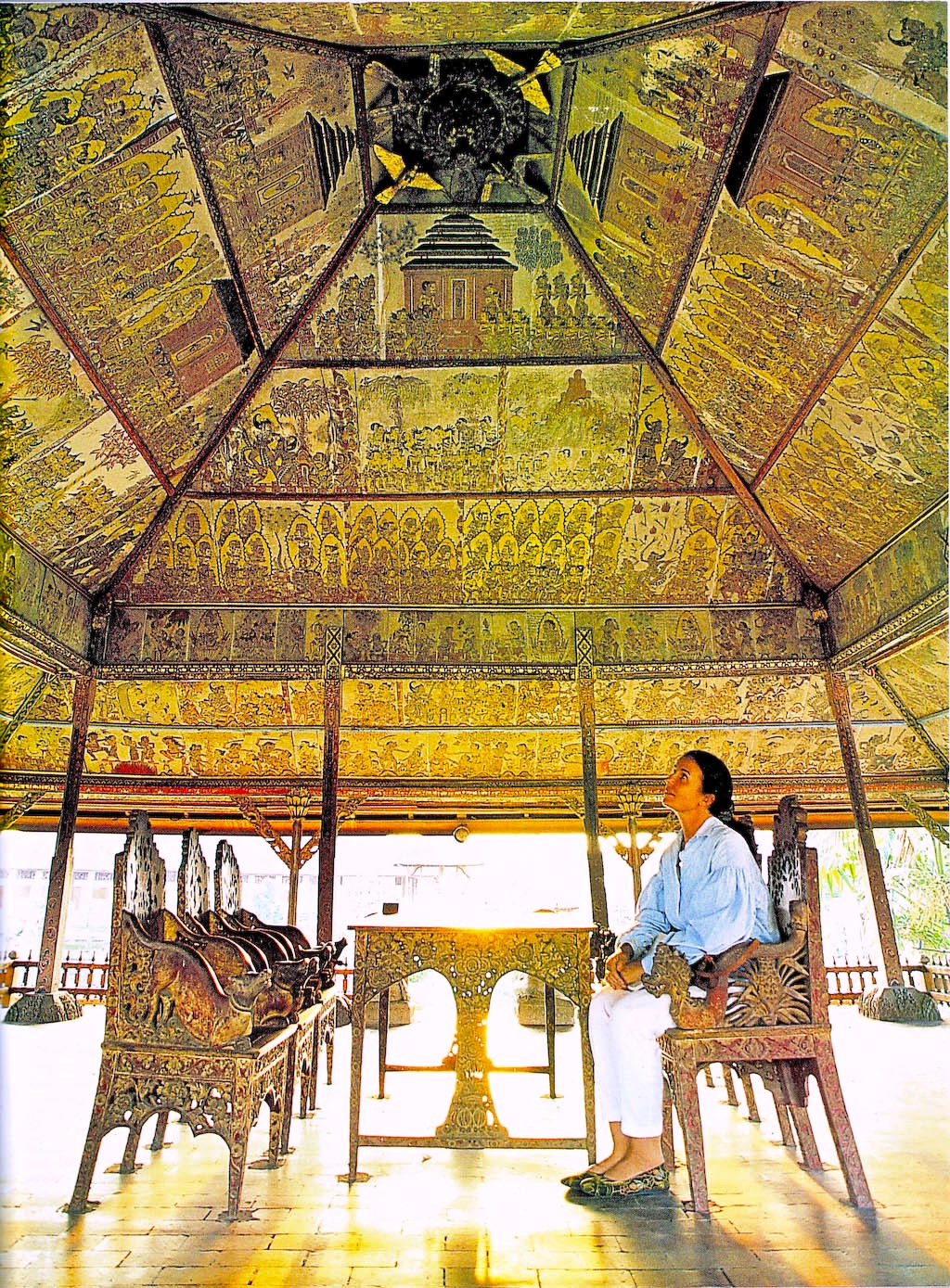

Over twenty years ago, I arrived in Bali, innocent to the unseen forces at play. My first explorations were filled with wonder at a culture where devotion, art and ritual blended together so effortlessly. Then, one day, my eyes fell on the ceiling of the royal court of justice, the Kerta Gosa of Klungkung. Above me were 144 spectacular paintings depicting the epic story of a mythic hero passing through strange worlds.

Intuitively, I was drawn to these images as I had been to Dante and his Divina Commedia years earlier, as a child growing up in Florence. My curiosity took slowly the form of an obsession: each painting revealed a story of divine judgement and the fate of souls, the Underworld and Paradise. Bhima, the hero of the story, belonged body and soul to the Mahabharata, the ancient Hindu epic. His quest was to enter the underworld to save the souls of his parents who had been wrongfully miscast. Two loyal servants accompanied him: Twalen and Merdah, the most beloved and popular characters of Balinese lore. Bhima became my guide into the punishments and fates that await sinners and saints in the afterlife, and taught me everything I know about the Balinese realm of the spirit.

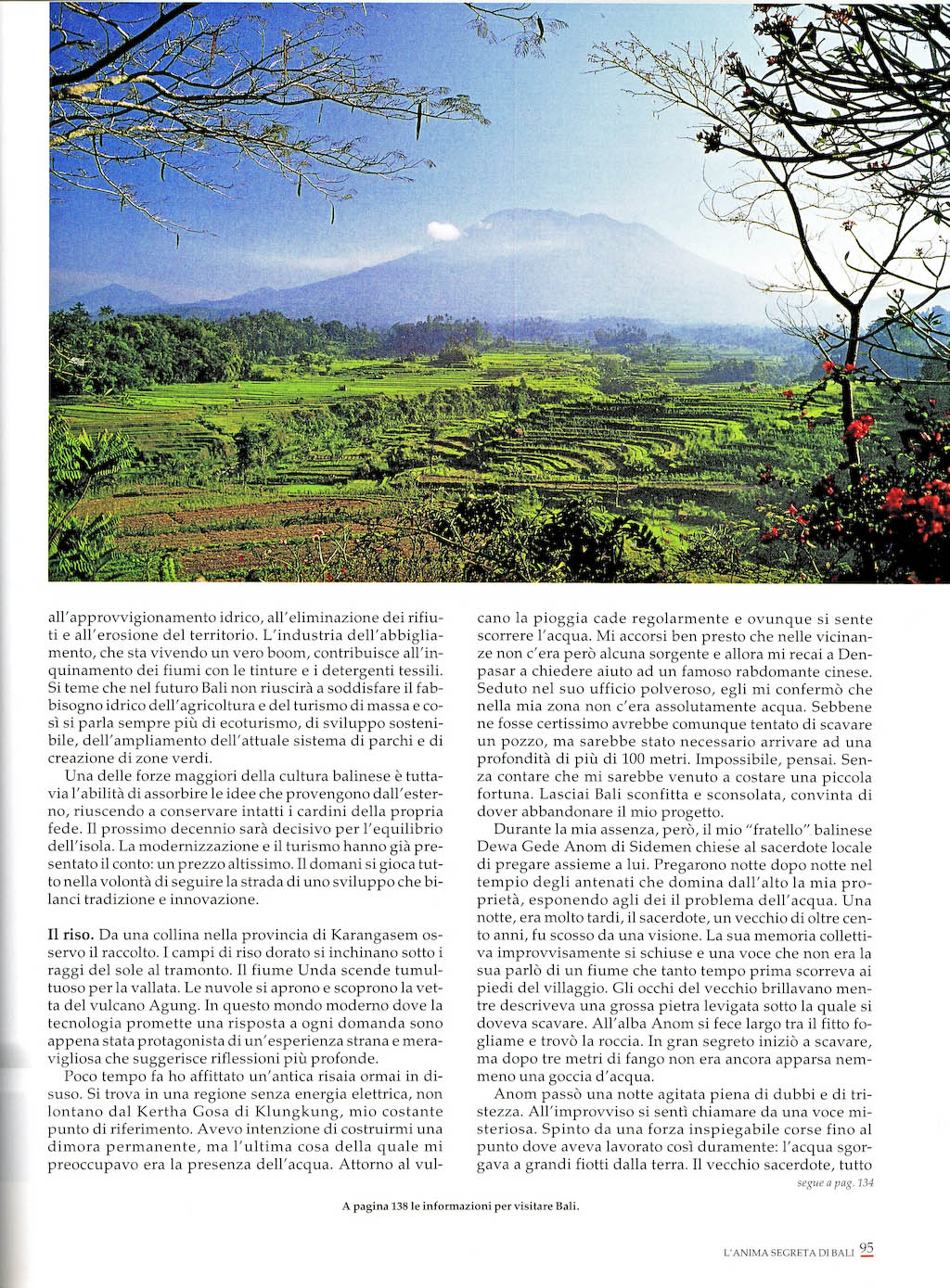

My search for the meaning of the paintings drove me to the green hills beyond Klungkung, into a land of power, untouched by the modern world. The dirt road snaked its way into the clouds. Rising steeply on each side were lavish ricefields like jade staircases built for giants or Gods. Climbing the winding road past Sidemen, I found a small abandoned house, once owned by Walter Spies, a famous German artist, who had used it as his hideaway to escape the flood of tourists flocking to Ubud in the Thirties. Here, he had found solitude and inspiration. And here, fourteen kilometers from Kerta Gosa, I settled.

Two parallel worlds soon opened all around me: the first was a rare landscape of drama and poetry that still takes my breath away. Never before had I seen nature and humans merge with such beauty. No bitter rivals here. The land had been carved and sculpted over centuries by caring hands. The second world opened more slowly: here I could not trust my eyes. Instead, I had to listen to the myths and see beyond the ceremonies for the Gods.

I soon learned that everything in the environment was seen as alive: the volcano, the water, the rice, and everything else. Hinduism in Bali is a thin veil resting over a profound animistic faith. Nature, in her many manifestations, is worshipped to its core: the gift of life. The volcano, the water, and the rice, are the three pillars of Balinese culture, forming a circle of faith around both the natural and the spiritual worlds.

Gunung Agung is not only the highest mountain on the island (3,142 meters), but it is also the sacred home of the Gods. Perched high in the clouds, clinging to the mountain’s slopes, are the two great mother temples of Besakih and Pasar Agung. For the Balinese, it is, quite simply, their Mecca. Visible from almost all areas of the island, it is the direction towards which worshippers turn to pray. But when people sleep, they take great care not to lie pointing their unclean feet in that same direction. All beds are positioned not to offend the gods.

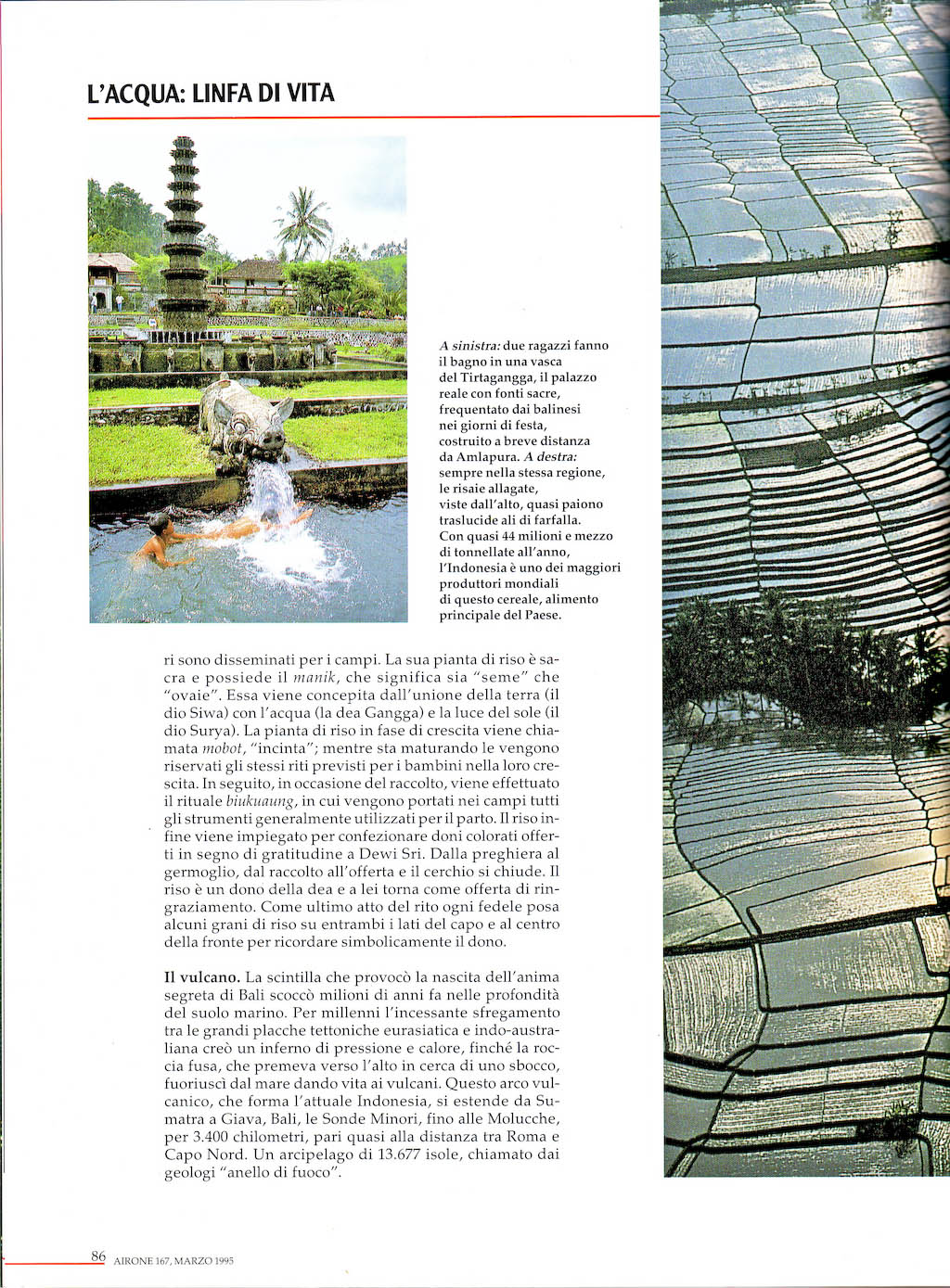

Similarly, water plays a crucial role in life and worship. Water allows the rice culture to flourish. The vast Indonesian archipelago, stretching east of Bali, more closely resembles dry, arid Sicily than a lush, tropical paradise. Returning from those islands, it is clear that in Bali the Gods have been kind. Water is everywhere and plentiful. It is the life force. So much so that the Balinese call their faith, Agama Tirta, “religion of holy water.” Holy water purifies all occasions. Before and after prayer, it is ritually poured by the priests into the outstretched open palms of worshippers to cleanse body and spirit. Together with the farmers, priests also plan and govern the distribution of water needed to irrigate the vast tapestry of farmland. Together, they weave a fabric revering water as a special gift. Without water, the entire culture would vanish.

Finally, there is rice. It is so important that the Balinese word ngajengang means both to eat and to eat rice. And within each grain of rice is the Goddess, Dewi Sri. She emerges from the seedlings to feed the Balinese people. Her temples and shrines are sprinkled throughout the fields of Bali. Her rice plant is sacred and possesses manik which means, at once, semen and ovaries. It is activated from the holy union of earth, in the form of God Siwa, water from the Goddess Gangga and light from God Surya. When rice is growing, it is called mobot or pregnant. As it matures, it is given the same rites as growing children. When it is about to be delivered, the biukuaumg ritual takes place, and all paraphernalia normally used in deliveries is brought into the fields for harvest. And finally, rice is shaped into colorful offerings in gratitude to Dewi Sri. From prayer to a seedling. From harvest to an offering. A full circle. The rice is given by the Goddess and, in thanks, is returned to the Goddess. In the final act of prayer, each worshipper places a few rice grains on either side of the head in symbolic remembrance of the gift.

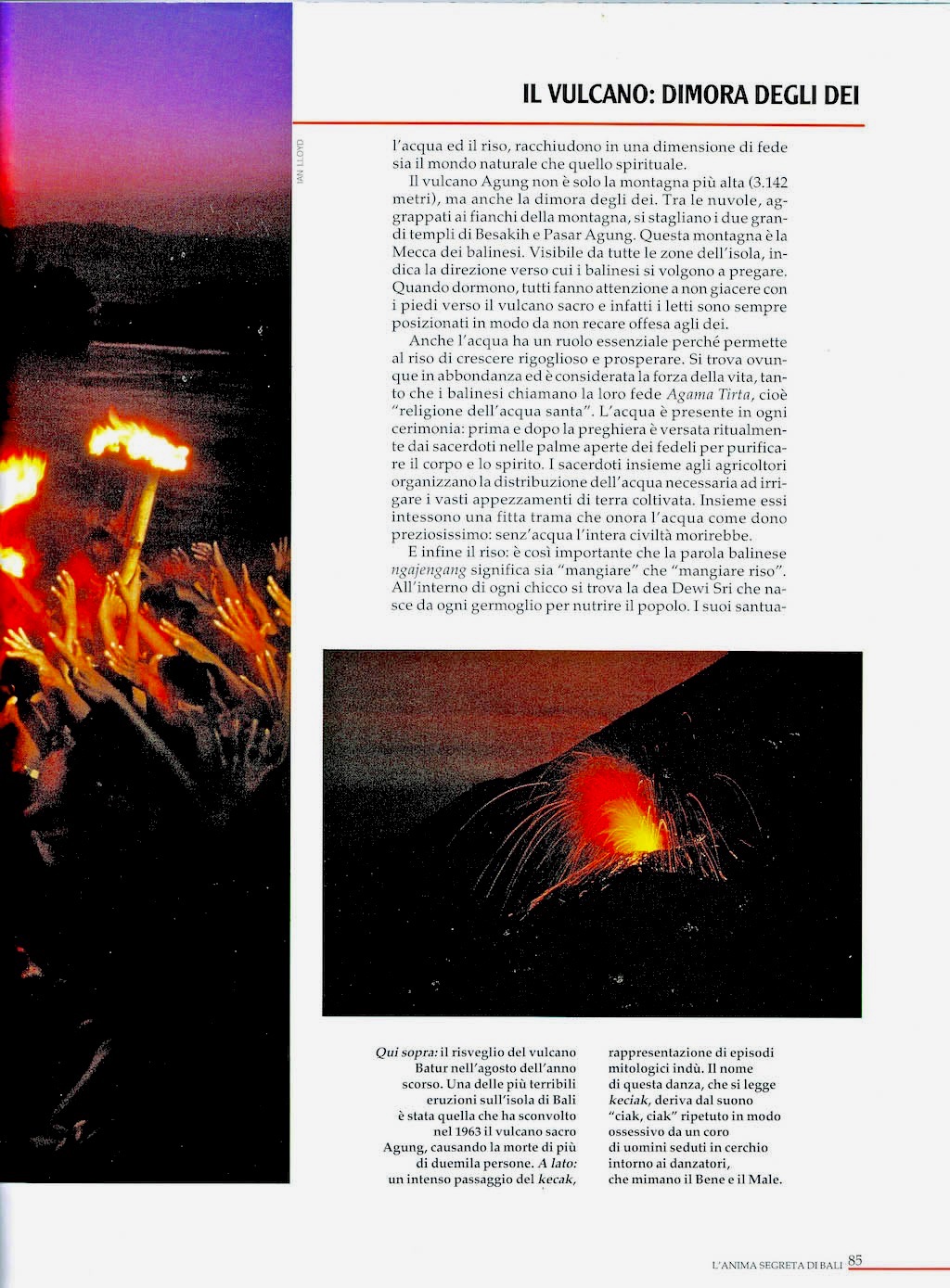

The spark of Bali’s secret soul was triggered eons ago deep beneath the ocean floor. For millennia, the thunderous clashing of the great Eurasian and Indo-Australian tectonic plates brewed an inferno of pressure and heat. The molten rock pushed upward for escape. Volcanoes burst out of the sea. The volcanic arc, which now shapes Indonesia, stretches 3,400 kilometers, from Sumatra, Java, Bali, the Lesser Sunda Islands, all the way to the Moluccas: the distance from Casablanca to Moscow. Geologists call it the “Ring of Fire”: an archipelago of 13,677 islands that has changed history in more than one way.

In 1815, as Napoleon was drawing his last breath on an Atlantic isle, Mount Tambora, on the island of Sumbawa, east of Bali, exploded. It was the largest eruption ever recorded, 150 times the force of Vesuvius that buried Pompei in 79 A.D., and ten times the force of Krakatoa. The following year was known as “the year without summer.” Crop failures led to famine and food riots, causing a near collapse of society throughout Europe and America.

As I write, Mt. Batur, in north Bali, is spitting out fire and belching smoke. In Java, Mt. Merapi, terrestrial home of Loro Kidul, the feared Goddess of the Southern Seas, is rumbling just like Mt. Rinjani in nearby Lombok. From distant Moluccas, news comes that Mt. Gamalama is shaking tiny Ternate and her gardens of cloves. Even Mt. Batukaru, in west Bali, long thought to be dead, is showing restless signs. Deep seeded fears are being awakened, not only in Bali, but throughout the archipelago. It is no wonder that on these islands, people take great care to appease the spirits of volcanoes. They are alive. The Gods are present. The Islamic or Christian or Hindu faiths have to reckon with the omnipresent forces of nature. It is understood that when the Gods are not pleased, a terrible price must be paid.

None in Bali have forgotten the ominous event of 1963, when the Gunung Agung exploded. Thousands died, miles of farmland were destroyed, villages buried. Anna Mathews, a British writer who was living in the region at the time, witnessed the eruption. In her book, A Night of Purnama, she describes how, during the chaos, a priest ordered his terrified son to flee from the temple. After running to safety, the boy turned to look back. He saw his father, dressed in sacred cloth, praying in the direction of the approaching lava. Soon, the temple was filled with villagers wearing their finest sarongs and jewelry, young girls adorned with flowers in their hair, and mothers who held babies at their breasts. As the lava advanced, the priest rang the holy bell and sang praises to Brahma, the visiting God, who was approaching. The boy watched as the lava spilled over the walls, covering the temple in black smoke. Not a single cry. When the bell stopped ringing, he knew that all his family and friends were no more.

Everyone in Indonesia knows that nature speaks always in violent tongues. Earthquakes and tidal waves wash away villages, volcanoes erupt changing the face of everything around them, droughts leave land dead and barren. People do not accept these acts as random calamities. Surely the Gods have a reason for displaying their anger. In Bali, the job of interpreting the logic of the Gods is left to a specialist. Like a cosmic psychologist, the priest explains the reasons as to why society has failed in the face of the Gods, and prescribes the ritual cure.

But in nature’s death, there is always rebirth. Volcanoes may kill but their ash enriches the soil. An alive, ever-growing mountain attracts more rain. The water, cascading down its steep slopes, will again create lush and fertile farming grounds. Ironically, the taker of life is also the giver of life.

I recently witnessed the consecration of a newly built temple on Gunung Agung, the result of three years of volunteer labor and funds raised all over Bali. The 800 year old site, home of the ancestral Gods of Bali, had been completely buried in the last terrible eruption. Resurrected to new life, the Pasar Agung is clinging to the cliffs, surrounded by pine trees. Its tall pagoda roofs, exuding the same spectacle of a Tibetan monastery, overlook the entire island.

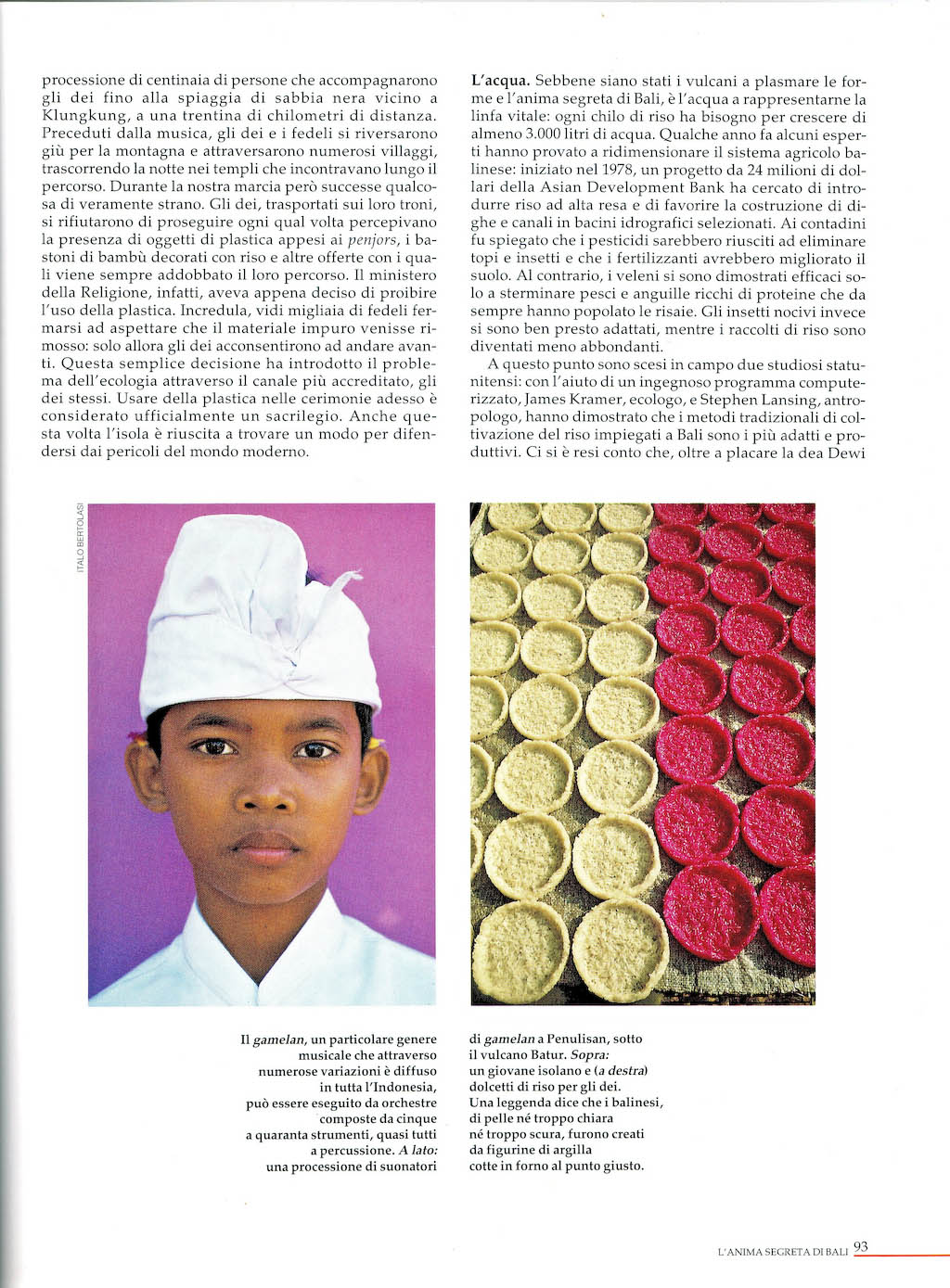

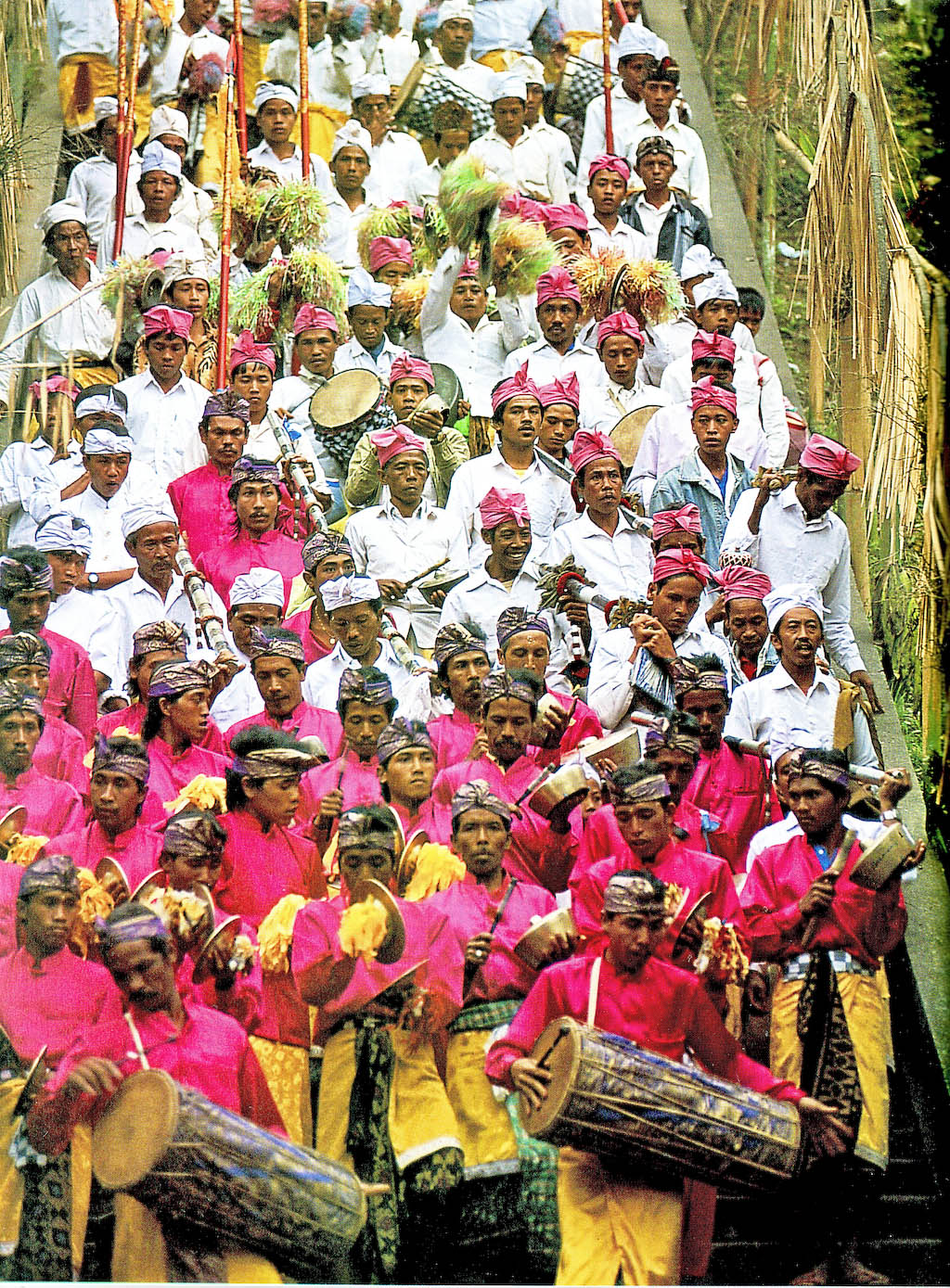

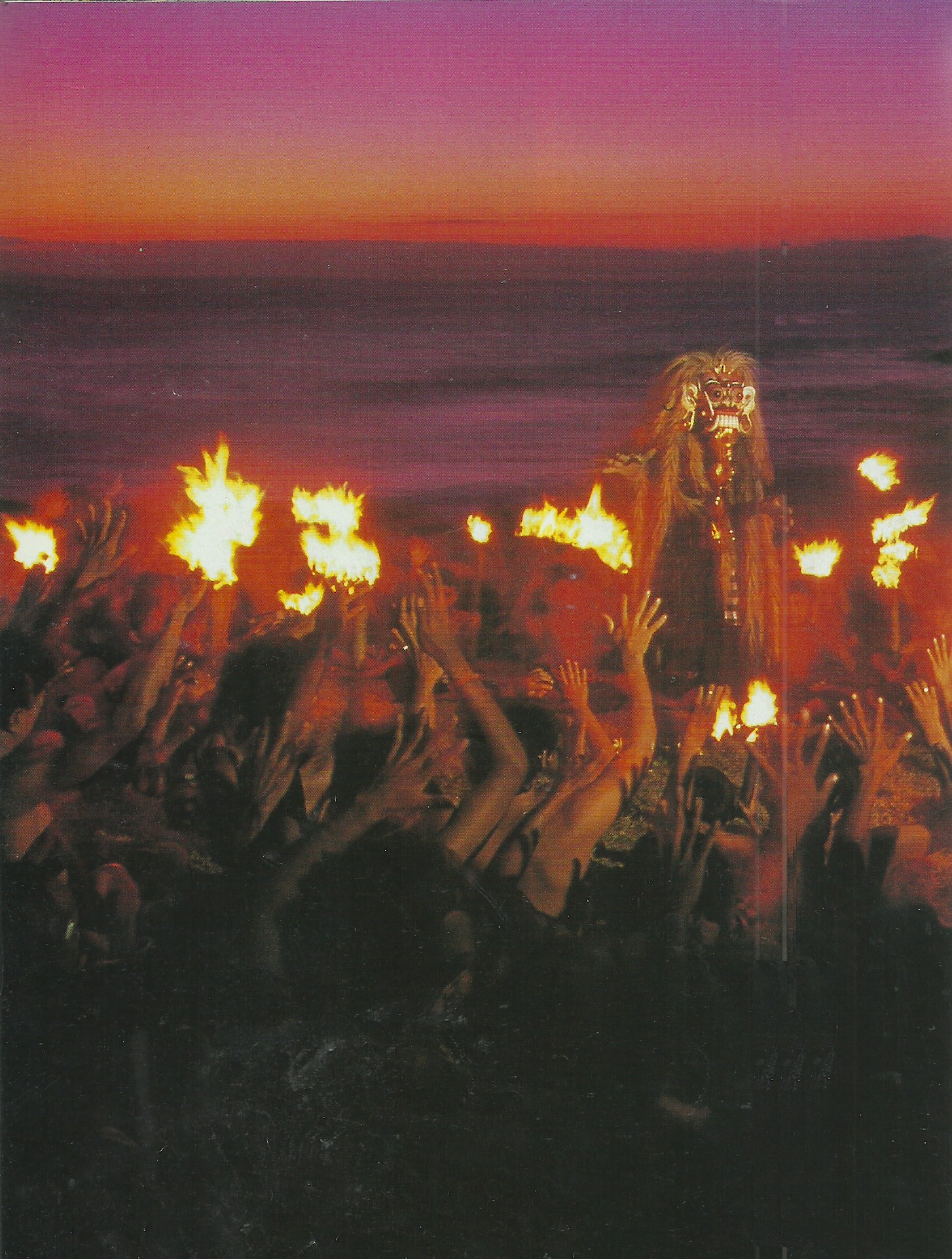

The celebration culminated with thousands of devotees accompanying the Gods on their first outing to the black beach near Klungkung, 30 kilometers away.Streaming down the mountain, the procession, complete with gamelan orchestras, passed through many villages, resting at night in temples along the way. But a curious thing happened during our march. The Gods, carried in their royal thrones, refused to continue on whenever they sensed that plastic was hanging from the penjors or bamboo poles, decorated with offerings and rice along their route. The religious authorities had ruled out all plastic. Only the island’s natural products could please the Gods. I watched in disbelief as thousands of people stopped and waited until the polluting material had been removed. Only then, would the Gods agree to go on.

This simple act has introduced ecology through the highest channel: the Gods. Plastic must not be used for ceremonies: it is now officially unclean. Continually, the island finds ways to cope with the invasion of the modern world.

Volcanoes have shaped the body and secret soul of Bali, but water is its life blood. For each kilo of rice, a minimum of 3.000 liters of irrigating water has been used. For this reason, rice farmers in Bali take great care not to offend Dewi Danu, the water Goddess who dwells in the crater lake of the Batur volcano. Toward the end of each rainy season, they send representatives to Pura Ulan Danu Batur, the temple at the top of the mountain, to make offerings in thanks for the water that sustains ricefields.

Modern experts have been questioning the Balinese farming system, trying to improve it. The Asian Development Bank designed a new 24 million dollar system, introducing high yield rice and building dams and canals in selected watersheds. The peasants were told that pesticides would take care of the rats and insects. Fertilizers would preserve the soil. But, the poison proved quite effective at killing off the protein-rich fish and eels that had always thrived in the rice paddies. The pests soon became resistant and the rice crop dwindled.

With the help of an ingenious computer program, American ecologist James Kramer and anthropologist Stephen Lansing, have shown that the Balinese rice growers are practicing state-of -the-art management. Besides pleasing the Goddess, it turns out that the island’s ancient rituals coordinate the irrigation of hundreds of scattered villages. The new computer model revealed that the Balinese peasant practices represent the most efficient farming system on the planet.

Hundreds of village-size farming cooperatives, called subaks, dot the island. They are linked through a network of temples extending all the way from the top of the Gunung Agung to the seacoast. If a subak wants to tap a new spring or divert water from a canal into its own field, it appeals to the high priest of the water temple. The priests do more than divide up the water. They are master ecological planners, helping the subaks juggle their planting schedules to conserve water, preserve soil and control the spread of pests.

As priests and government officials played with the computer program, they quickly discovered that the richest possible harvests involved Bali’s traditional farming scenarios. By the time the Asian Development Bank formally acknowledged that fact in 1989, many of the peasants had already reverted back to their old ways.

But if the ecosystem and natural resources of Bali have been macro-managed by ancient tradition with incredible efficiency, there is still a threat greater than the advice of modern experts. It is mass tourism. In 1993, over 885,000 foreign tourists vacationed in Bali, with 35,000 Italians among them. A vast complex of hotels with golf courses has recently been built to accommodate the booming demand for luxury. Precious water must now be diverted. It is estimated that one tourist consumes 40 times the water of one Balinese villager every day. In Denpasar, the capital city, water pressure is often reduced so that pressure can be maintained for the hotels and the many swimming pools scattered along the southern coast. Current government forecasts speak of 2.5 million tourists arriving on the island by 1998, with the need for an additional 48,000 rooms on top of the present 26,000. If this happens, foreign visitors will almost equal the island’s present population which is just under 3 million.

Against this pressure on finite natural resources, ecological issues have now become emerging concerns. There is a steady loss of agricultural land to tourist developments and urbanization. Coral reefs have been destroyed for building material. Some hotels have been built without fully considering water supply, waste disposal and erosion. The booming garment industry is polluting local streams with fabric dyes and detergents. There are doubts that Bali will be able to provide adequate water for both agriculture and mass tourism in the future. There is talk of eco-tourism, sustainable development, enlarging the current park system and establishing green belts. Programs for a clean environment have been launched in villages. On the coast, it is a race against time.

However, one of the great strengths of Balinese culture has been its ability to absorb external ideas while maintaining its central beliefs. The next decade may well be the island’s greatest test. Modernity and tourism exact a huge price. But for most Balinese, changes have not yet drastically transformed their lives. More than 70% of the population is still rural, devoted to farming as well as sculpting, painting, weaving, and the performing arts. At the core of their sustenance is the crop of rice with the mandatory rituals to the Goddess Dewi Sri.

In the province of Karangasem, I sit on a hillside, observing the harvest. Golden fields of rice droop in the setting sun. The Unda River, fresh with rain, hurls its water down the valley. The clouds break, revealing the peak of Gunung Agung. In this modern world, where technology promises all the answers, I have just experienced a strange and wonderful event that suggests the contrary.

Recently, I leased a small piece of land that was once a rice paddy, near a village that still has no electricity, not far from the Kerta Gosa of Klungkung, my main point of reference. My intention was to build a more permanent house in the same region. But the last thing I thought of was the question of water. Rain falls around the volcano and sounds of water are everywhere. By the time I discovered that there were no water springs nearby, it was too late. There was nothing I could do. In a panic, I went to Denpasar and asked a renowned Chinese water expert and well driller for help. In his dusty office, he confirmed that there was absolutely no water in my area. In spite of his pessimism, he added that he could try but he would have to drill at least 200 meters: the height of the Duomo in Florence! Impossible, I thought! And all that for a small fortune! I left Bali dejected and defeated.

During my absence, the local priest prayed on our behalf to find water. In the rice temple above my land, night after night, he prayed, asking guidance from the Gods. He made offerings under the full moon and waited for a sign. Late one night, the priest, who is over 100 years old, was shaken with a vision. His collective memory suddenly opened. A voice, not his own, spoke aloud of a river that once upon a time had flowed below the village. His eyes glowed as he described a large polished rock where one should dig. At dawn, his son Pak Merta made his way through thick vegetation and foliage and found the rock. He began to dig in great secrecy. But after three meters of mud, not even a trickle of water appeared. He spent a troubled night filled with doubts and sadness. What to do? No water. No hope.

Suddenly, he heard a haunting voice echoing his name. Outside it was still dark. All was silent. Pulled by a force he cannot explain, he ran all the way down to the site where he had worked so hard. There he stopped in awe. Water was gushing out of the ground like a bountiful fountain. The old priest, all dressed in white, appeared from the shadows. He sat down on the bare earth and prayed.

Now, there is enough water for the entire population–about 500 people–and for my home. The women are spared their daily half hour trek down the hill to the river and back. Instead, they fill up their buckets around the corner at the two fountains, erected as part of our aqueduct. The face of the old priest beams with a knowing smile. Repeated tests have shown that what was found, thanks to the Gods, is pure mineral water. Word of the miracle has spread up and down the valley, all around the region. People say that the Gods have blessed us.

When I returned to Bali this time, I made my usual pilgrimage to the paintings of the Underworld and Paradise, which now are visited by hundreds of tourists. No longer in need of Bhima, my epic guide, I drove beyond Klungkung, towards the slopes of the Gunung Agung. Far from the madding crowd, far from the beach resorts, high in the clouded hills, I reached my new land. Pak Merta was waiting. He greeted me with the biggest smile I have ever seen and led me to the magical spring below the village. The site had already been honored with a shrine. Covered with offerings, it had already joined the family of Bali’s 20,000 temples. Now, people come here to pray. With delicate gestures, young girls sprinkle holy water onto the colorful offerings. Lying in the sculpted banana leaves, are always the rice grains of Dewi Sri.

By the time, we walked back, it was dusk, and the road was deserted. The entire village was packed in the temple, celebrating the Gods. As we approached, the sound of the gamelan became more distinct. The temple was all dressed with flags and decorations. Dancers were putting their make-up on and flowers in their hair. Gold glittered from their costumes. The old deaf priest, thanks to whom the water had been found, looked as ancient as his eyes were youthful, glittering with energy under a veil of incomprehensible distance. His lips were turned into a permanent suggestion of a smile, even as he prayed seriously, fingers curled up like frangipani branches in prayer, still able to handle the tools of his trade, holy water and flower petals.

The secret soul of Bali was powerfully intact, safely hidden inside his collective memory, where past, present and future were locked into one eternal union. In a short time, his soul will either return to earth in the child of his great-grandson, or come to rest in the eastern direction of Swarga, the Hindu Paradise, where the souls of Bhima’s parents finally settled, safe from the dangers of the “Ring of Fire.”