In his magnus opus, The Alexandria Quartet, Lawrence Durrell describes Emilio Ambron’s city of origin: “She’s there like a natural spring, not to quench the traveler’s thirst, but to awake his most intimate desires in the forever unquenchable quest for love…” He compares Alexandria to a voluptuous woman “with eyes like dead moons.” But the city could also be called “Clea” like the artist who pervades the last movement of the Quartet. Clea is peaceful and serene in her studio, painting. She glides through Durrell’s imagination with elegance, temperance, and sensuality. A personification of desire and companionship, she may well be the composite of two women, Amelia Ambron, and her daughter Gilda, Emilio’s mother and sister, both of whom Durrell befriended during his sojourn in wartime Alexandria.

Amelia Ambron was an artist who made magnificent charcoal portraits; Gilda was also a remarkable portrait painter who preferred to work with oils; while her other daughter Nora was a promising violinist; and then there was her son, Emilio, a born artist as well, whose long journey into art is honored in this book.

Aldo Ambron, Emilio’s father, a civil engineer, was incredibly proud of his family. He thrived on their talent and became the patron of his four artists. He had vast means and could give his wife and children the privilege of the best artistic education that life could offer in both worlds, his adopted Egypt and his native Italy.

In Egypt, the Ambrons lived in a mansion with a tower and a vast garden in the Jewish quarter of Muharram Bey in Alexandria. Their sense of hospitality was well known. Cavafy, Marinetti, Claude Monet, Ungaretti were household names. In the garden, Amelia had her spacious atelier. At one point, the tower was rented out to Lawrence Durrell, a British writer.

“I have furnished myself a Tower where I have finished one book of verse [Personal Landscape,] and am half-way through a book about Greek landscape [Prospero’s Cell]…” wrote Durrell from the Ambron house in a letter to his friend Henry Miller. The date was February 8, 1944.

The ambiance of the setting together with its cultured, sophisticated landlords enabled Durrell to enter into Alexandrian life and society, drawing material for his masterful descriptions in his Quartet. Durrell’s two and a half memorable years in the Ambron tower marked him forever and gave world literature one of the great masterpieces of the twentieth century.

In Italy, the Ambrons owned a grandiose residence in Rome. Here too Amelia had her atelier in the garden. It was in this neighborhood of Parioli that Emilio, at age 15, began his daily visits to the studio of the great Futurist Giacomo Balla who became his teacher. Six years later, he had his first exhibit in Alexandria. And by the time Durrell became a tenant of the Ambrons, Emilio had become a mature artist possessed with an unsatiable curiosity for discovering new landscapes, shapes, and forms. By then, he had left both Alexandria and Rome, sailing off to Bali in the Dutch East Indies. Unable to return because of the war, seven years passed before he could make his way back safely to the warmth of his family home in Alexandria. Emilio Ambron was now 42 years old.

A master of drawing and a citizen of the world, Ambron did not choose Egypt as his base, but Italy, where he had spent on and off his formative years. He bought a spectacular atelier in the heart of Florence–formerly believed to be the studio of Salvator Rosa, the seventeen century painter. He commuted between Florence and the family estate in the Siena countryside. Only in Tuscany, he could live in communion with the great masters of the past still alive in the present.

It was not in my native Florence that I had the privilege of meeting him, but in the island of Bali, many years after it had ceased to be a Dutch colony. He was accompanied by his wife Carla whose delicate features always inspired him. It was our passion for Balinese art and culture which united our kindred souls, despite the great difference in age and experience. Ambron had lived in Bali from 1938 to 1942. By the time I met him, about thirty years later, his name and work had become part of the island’s history. I was in my early twenties and I had just discovered the hypnotic wisdom of Bali’s fables and myths. These stories, passed down from father to son, endow the society with the capacity to adapt to the times without losing either spiritual energy or creative drive.

Like the Balinese, Ambron was brimming with stories and imagination. A word was enough to set him off and, as if by magic, one found oneself on a tour of the world which, via Alexandria, Paris, Denpasar, Shanghai, Angkor, on to Saigon, and back to Alexandria, always ended up in Florence. While listening, one immediately felt confronted by a great personality, culturally and artistically, an ebullient man, larger than life, belonging to a rare human breed now in extinction.

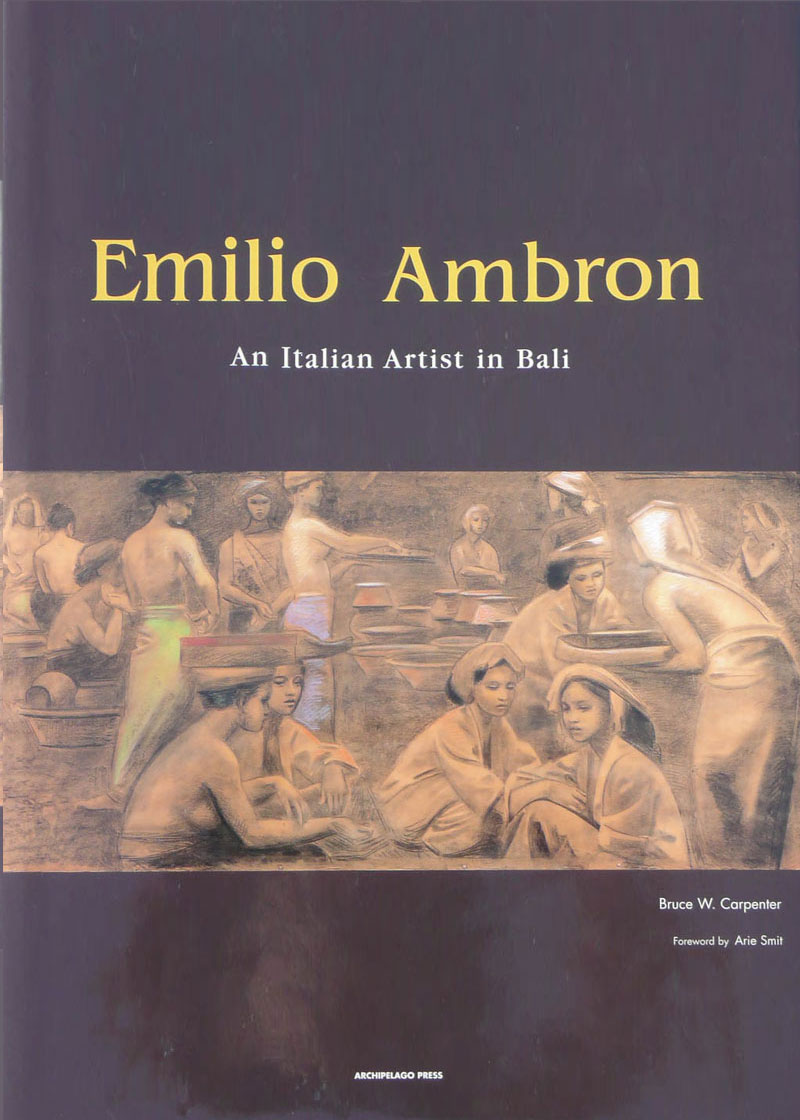

A tireless observer of aesthetic expression, he followed its movements, pace, and positions. Obsessively, right up to the end, he continued with his pencil or brush to freeze a gesture, a glance, the instant in motion, seizing the inner pulse of life’s silhouettes.

It is indeed an honor for me to pay homage to the memory of such a master of art, a man who made of life itself an art. I trust that this book along with his work will serve to encourage young artists to develop solid foundations before taking their creative flight.

In the present age of ever-increasing opportunity for communication and exchange between peoples and cultures, it gives me great joy to know that Ambron’s donation to Bali–69 works in the mediums of stone and bronze, pencil, charcoal, and oil–will be permanently on display at the Museum Semaraja on the grounds of the royal palace of Klungkung, ancient Renaissance capital of Bali, visited by multitudes of Balinese as well as tourists. This donation was his farewell to the world just before his death in June 1996, at the age of 91.

Among all the foreign artists who have worked in Bali, Emilio Ambron is the only one who received the honor of preserving his art in the most revered temple of traditional Balinese culture. Now, he lives on in the company of the highest among the island’s ancestors. His art, influenced by the classical Renaissance style, has become a source of interest and inspiration for the new generations. While most art students in Bali have heard the names of Leonardo and Michelangelo, few have seen examples of Renaissance art.

The Ambron donation represents an ideal bridge between our two cultures–Tuscan and Balinese. At first glance, these appear to have little in common, but in fact are strangely linked by analogous artistic phenomena and certainly a legendary past. Both are cultures favored by a magnetic pull that creates economic wealth by attracting visitors from all over the world. And both have similar environmental, urban, and conservation problems.

Few people know that concealed here and there in Florence are Balinese secrets and Indonesian treasures. The first European tourist to travel to Bali at the closing of the 19th century, was a Dutch artist, historian, and great collector of Balinese art by the name of W.O.J.Nieuwenkamp who later chose as his residence a villa in Fiesole, and is buried in the small cemetery of San Domenico. In 1890, the Florentine naturalist and ethnologist Elio Modigliani embarked on a groundbreaking journey to the Bataks of Sumatra, for the first time reaching and studying the amazing island cultures of Nias, Enggano and Mentawai. With the great British naturalist Russell Wallace, who traveled to the furthest corners of the Malay Archipelago, Modigliani remains the only scientist who ventured all the way to those remote lands.

In more recent times, Balinese culture also influenced another notable Florentine, a member of my own family, the designer Emilio Pucci–whom I like to remember as an anthropologist of fashion. He owes to Balinese culture his 1962 collection which launched his remarkable career. Presented in Florence to an international audience of journalists and buyers, densely packed in the Sala Bianca of Palazzo Pitti, the collection was entirely inspired by Balinese dance and traditional costumes, iconography and colors. The Indonesian Batik design, blending geometry with flowery motifs, would influence his entire concept of design.

Emilio Ambron, who knew my uncle, and was well acquainted with both Nieuwenkamp and Modigliani, will always be an intrinsic part of the hermetic side of Florence, the unlocked treasure-box always ready to embrace those who love cultural challenge.

While Ambron’s forever missed mother and sister, Amelia and Gilda, will continue to live on in Durrell’s unforgettable character of Clea who stares across the Alexandrian surf, the spirit of the maestro dwells in the heart of the two most important places in his artistic life: Florence, the city of the red Lily on a white background, and Bali, the mythic island of artistic dreams. Brushes, jars, chisels, knives, oil, pencils, marble bronze, and canvas, all lie where the Maestro left them that final day, when his wandering Mediterranean eye stared into the ultimate muse.