My brother Giannozzo always says: “Florence is a hermetic city. One should never stop searching and looking beyond appearances … Then, when you least expect it, something unpredictable, absolutely inconceivable emerges.”

And this was exactly what happened. I was unaware of the treasure which had always been there behind a gate, beyond a stone wall with the usual three lines of barbed wire.

In Asia, people say that nothing happens by chance. Well, I wonder. In Florence, you need Ariadne’s thread to reach where you must arrive, and a pinch of luck as well.

After such a long time spent in touch with the Indonesian island of Bali, where I settled some thirty years ago, I wonder now how, in my childhood, I could have made friends with two of W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp’s grandchildren without ever knowing about their special grandfather. How could I have imagined that one day he would become an icon for me? And to think that my friends lived in his house. It was only years later that I discovered that they used to run wild in the enchanted garden, on the slopes of Fiesole–in the very garden he had created with the same love with which he drew the animated trees from the island of Bali that had bewitched his soul.

But I never ran in that garden as a child. So how could I have known that the daily life of that place, so drenched in the spirit of Balinese art and culture, failed to stir any curiosity in Nieuwenkamp’s own family? I understood why only later. Their grandfather’s world belonged to him alone and he could not share it with anybody. The children saw him from afar when he strolled along the garden paths or when they were told to be quiet as he retreated into his studio. For Nieuwenkamp, his grandchildren were a source of disturbance.

One day in 1950, this solitary artist who had abdicated his grandfatherly role fell asleep for ever. Yet, his presence continued to permeate the villa and the garden, dominated by an immense bronze gong from the gamelan, which still keeps vigil over the entire property.

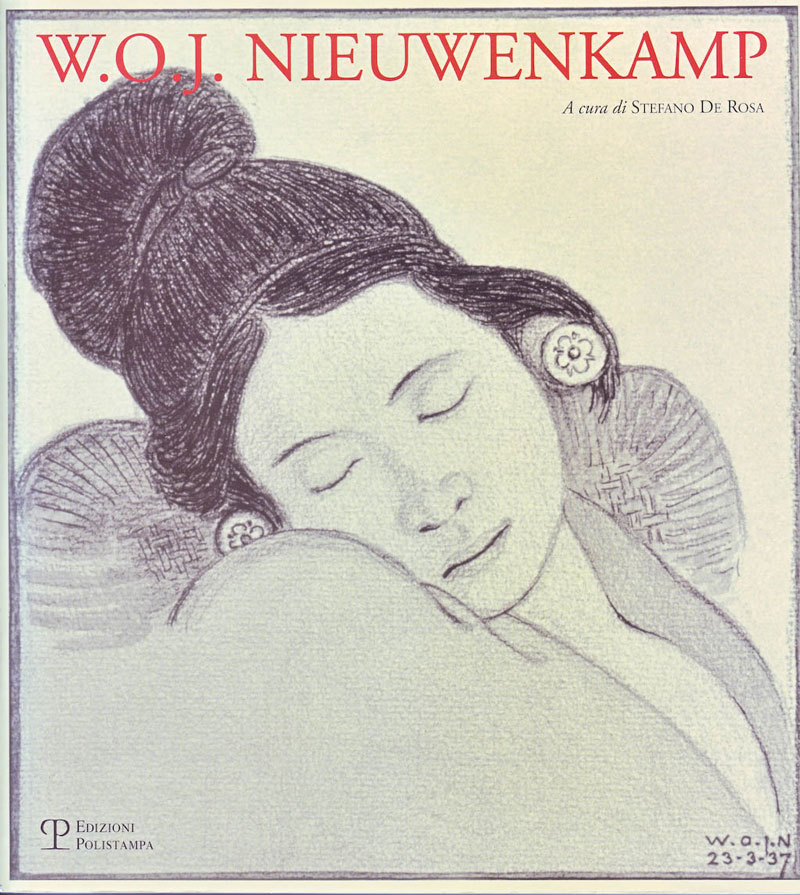

Most of the art collection was safely stored in his legendary trunks branded with his great initials–W.O.J.N–and the labels from the “Bali Hotel,” the island’s first rest house, where his stayed during his last voyage in 1937. The trunks were stacked together with his works–a treasure of drawings, oil paintings, diaries, books, photographs. It all was stored in the semi-obscurity of a room that soon became as mysterious as a forgotten attic. Everything else–even the Balinese inlaid doors or the tiles with symbols and friezes copied from Balinese temples; wooden and stone votive statues; as well as a great lotus-shaped fountain, the oriental holy flower that seems to float magically on the water–continued to be part of the property, known as “The Bishops’ Resting Place”– Il Riposo dei Vescovi.

Like the eminent high priests of the past who had halted there on their way up to Fiesole, Nieuwenkamp had found in this magical place a haven of peace, far from his austere native Holland. Here, at the gates of Renaissance Florence, the cradle of artists and artisans, he had found the perfect counterpart to the extraordinary Balinese culture that had captivated him.

Vagando Aquiro, “By Wandering, I Discover” was his life motto. And so it was, that after his death, the spirit of Nieuwenkamp, citizen of the world, retreated into hermetic Florence. In truth, he was destined to become a hidden treasure already upon his arrival in 1926. Nobody in Florence or in Fiesole took any notice of him and he probably didn’t even realize it, because he lived apart, like many foreigners do, buried in his work. Every now and then he would open his gate to visitors from Holland or other parts of the world.

In time, the refined composure of his garden no longer held out against the changing seasons and yielded to its natural fate. But, the three hundred metre long cypress avenue continued to descend harmoniously towards Florence, cutting a swath through the land. From the sky, the three hectares of orchard, vegetable garden, olive grove, stone walls, hedges and towering trees reflected the union of macrocosm with microcosm like a great oriental carpet gently resting on the Etruscan hill. Nieuwenkamp’s aloof universe went on existing in an independent state.

It was my uncle Emilio who first told me about Bali. I can’t really remember when, but I believe I was about eight years old. Few Western people in the late Fifties ventured as far as the Indonesian islands. The airport in Bali, he said, was a little track over a grass meadow, with a thatched hut near a long beach. At sunset, my uncle Emilio had seen enormous flames soar out of the sun, fall into the sea and then reflect for miles around, until they touched the peaks of the great volcanoes.

In Bali, he was a guest of the art patron Tjokorda Sukawati of Ubud, in the centre of the island, in the same palace where, half a century earlier, in 1906, Nieuwenkamp had stayed on a long visit.

He too, like Nieuwenkamp, had been fascinated by the colours, textiles, ceremonies, music, the graceful dancers, and the powerful force of nature–by virtually everything else he had seen.

I listened carefully. He was not telling me a fairy-tale. These things really existed! And I was reassured that there were places in the world so different–and yet as wondrous and hermetic-as my own surroundings. I slowly felt a veil lift from eyes and a future with immense horizons stretched before me.

The fashions designed in 1962 by my uncle were entirely inspired by Indonesia. They marked the beginning of his brilliant career as fashion designer. It was Emilio Pucci who first created the wrap-around skirts, like the Balinese sarongs; and dressed his models in delicate tightly-fitting blouses in the style of Indonesian kebaya; and then told them to walk like Balinese girls in a temple procession. Perhaps it was then that his vision of fashion, so ahead of time, took shape. His geometrical and floral patterns–divided into well-defined sections—permeated his artistic creations. In an explosion of colour and cultural symbols, abstract and figurative mixed. I believe that his signature style flourished after his first journey to Bali and Java.

He too had been captivated by the beauty of batik. While Nieuwenkamp collected textiles like amulets, fascinated by their magic meanings, and often included them in his drawings, my uncle Emilio reinterpreted the motifs of these fabrics, printing them on silk as fine as Ariadne’s thread.

And while living memories of Bali had settled on the slopes of Fiesole, down in the heart of Florence where I spent my childhood, Balinese iconography was transformed into “made in Italy” and then exported by Emilio Pucci internationally.

As fashion-conscious women squabbled over his head-scarves and his multi-coloured dresses, none of them probably realised that the patterns printed on silks and cottons had been conceived not only by the designer’s creative impulse, but also by an ancient Asian culture.

His two-fold talent of designer and ethnologist, I think, was at the foundation of his artistic originality. This fascinating aspect of his art remains almost unknown, as if a secret code were needed to decipher it, and like Nieuwenkamp continues to rest inside hermetic Florence.

When I came to fully realise this, it was too late. My uncle was already towards the end of his life and I did not have the time to complete my study of all his Javanese and Balinese inspired drawings. After his death in 1992, these astonishing symbols disappeared into an archive that I no longer was able to access.

By then, I had been living in Bali for many years. I felt at home in the island “sacred to gods and men”, as if I had grown up there. Oddly enough, everything seemed familiar. Florence was far away. Occasionally, I would go back briefly to see my father and brother, and perhaps also to persuade myself that I should not totally part from my ancestral city.

During one of these short visits, I met in the street a friend, Francesco Bacci, the son of a renowned Florentine painter, Baccio Maria Bacci. I had just published a book in America about Balinese mythology which told the story of a “Dantesque” journey through the Hindu-Balinese hell and their illuminated paradise. Strangely, he had just seen my book and congratulated me. Then he asked:

“Idanna, have you heard of Nieuwenkamp?”

“No,” I replied.

“What do you mean? After so many years in Bali, you must have heard of him! Don’t you know the Bramanti brothers, in San Domenico?”

I answered yes, of course. I had met Luca and Anna when I was a child, but had not seen them since. He then told me that this Dutch gentleman by the name of W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp was their grandfather.

“He was a great expert on Bali,” added Francesco, “an untiring collector, the first Westerner to carry out research on Balinese culture, and what is more, a very well known artist in Holland. His villa in Fiesole contains perhaps the most interesting collection of Balinese crafts… but nobody knows anything about these things in Italy, no one is interested ….”

I was stunned. I felt that I had stumbled on something that had always been there, right in front of me. Three days later, I stood at the gate on via Vecchia Fiesolana. Under my arm, I carried a copy of The Epic of Life, my “Balinese Divine Comedy” for Mrs. Fernanda Bramanti, one of Nieuwenkamp’s three daughters, and mother of my childhood friends. It was 1986.

That afternoon, I entered the artist’s secret world and have never left it since. A thread of fate led me into his garden, and the circle, started in my childhood, began to close. Bali had always been there for me, even in Florence.

Suddenly, I lifted my eyes and saw his figure in a terracotta bas-relief, embedded in the villa wall, surrounded by a profusion of jasmine. He was clothed in Balinese ceremonial dress with a sarong and the ritual kerchief knotted around his head. Yet, he also wore a European jacket. Riding a bicycle, his back wheel had blossomed into a flower–like a tropical zinnia–while his front wheel held many flowers, instead of spokes. And, to my surprise, I recognized this cyclist.

Many years before, on the northern coast of Bali, I had seen the same bas-relief in the volcanic stone of the main shrine of Maduwe Karang temple. I had even photographed it. What was this funny European figure doing, I had wondered, embedded in a temple wall? He surely must have left good memories in the village. Balinese never do anything without reason, especially on sacred shrines. But, nobody in Kubutambahan village was able to tell me anything. All they said was: orang belanda, a Dutchman. That was not such a reliable answer, because in Bali the word belanda refers to any foreigner, even sometimes to someone from another island.

The cyclist belonged to the history of the place and that was all. The people who had known him were dead. The master stone-carver had cut his silhouette as if he was an ancestor, whose memory should not be allowed to vanish. This greatly impressed me. What on earth had this “man on the bicycle” done to deserve respect?

Donato, a grandson of Nieuwenkamp whom I had never met, noticed my surprise. “My grandfather used to travel around Bali on a bicycle,” he said. “The villa is full of these terracottas he made, based on a stone carving which represents him over there….”

So, it was in Florence, that I found my answer to the enigma of the mythical cyclist I had once visited near Singaraja. Balinese culture confronted me at every turn in “the Bishops’ Resting Place”. Here, in the villa, was so much that had been swept away in Indonesia by the dramatic monsoons of recent history–the struggle for independence from Dutch rule followed by the Japanese occupation during the Second World War; and the events of 1965 that toppled Sukarno, ushering in unspeakable slaughter.

Here in Fiesole, I found a preserved time capsule of Balinese traditional culture before any contact with the outside world. The pieces originated from an earlier age when mass tourism was inconceivable, when airplanes and plastic had not been invented, when farming was all organic, and fresh water was the natural right of every human being. Nieuwenkamp had been the first Western eyewitness of this highly sophisticated society. He, then, became its supreme messenger.

I began then to understand why the Balinese had sculpted his portrait for future generations to remember. The “man on the bicycle,” in the context of his historical period, was certainly out of the ordinary. In the numerous books and diaries he left behind, never once does he give the impression that he felt superior to the people he met on his travels. Everything surprised him in Bali. Everything was an endless source of knowledge. He respected the smallest details of the customs and the peoples he encountered. His Western viewpoint never dominates. He simply tried to transmit the talent of the Balinese people, whom he considered “blessed.” This he did with extraordinary sensitivity, without any prejudice or the slightest trace of racism. He felt he had everything to learn and nothing to teach. His overall goal was to enlighten his Dutch compatriots about a marvellous culture that deserved their greatest respect.

At the height of the colonial age of imperialism, his behaviour was a radical exception. Nieuwenkamp reacted with heart and humanism, as a free man. This is why he became an icon for me.

Now that fate has brought into my home many of his surviving works, I feel immersed in the jungles that dominate his oil paintings. Nieuwenkamp’s representation of nature is vividly animated. Like the Balinese, he too was in contact with the invisible. Still now in Bali, the rustling of the leaves in the night is as alive as every grain of rice, or the devastation of incandescent lava. Nieuwenkamp, like the Balinese, felt embraced by the mystery of the universe, and never questioned it.

In his paintings, human beings disappear into the awesome folds of nature. In his drawings, instead, man is artist and craftsman–a being who creates and restores whatever nature’s calamitous upheavals have taken away or destroyed.

It is not a cliché to say that the average Balinese is a born artist. It is enough to look at the masterfully sculpted rice-terraces. This also explains why Nieuwenkamp was able to wander around the island in peace. He spoke the same “language” of the inhabitants. Normally diffident and highly superstitious, they accepted him. Full of admiration for his drawings, they were surely fascinated to see elements of their daily life–even a wooden bolt of a door or a water-jug–treated as works of art.

Armed with only drawing paper and pencil, Nieuwenkamp never tired to observe and record details of local architecture, rituals, gestures, and the ingenuity of the artisans. His obsessive work made him immune to the mysterious workings of black magic that still today pervade the island.

Through his humanity and art, he even managed to get the Balinese to welcome him during the bloodiest moment of the island’s occupation by Dutch colonial troops in 1906. With his art, he created a bridge of tolerance and understanding, and later publicly denounced in the Dutch press his countrymen’s ruthless aggression in Bali.

However, whenever he returned home to Fiesole from his long spells abroad, Nieuwenkamp’s free spirit strangely seemed to fold inward. The good-humoured communication and ease of contact that he enjoyed in Bali, curled up and hid in some corner of his personality. In Fiesole, he stayed alone in his studio, removed even from his own family. He took refuge in the activity that followed each trip. Alone, he would draw inspiration from his memories. As always, his muse lay in distant Indonesia.

“Once you have lived in this place, you can never be sane again, you are driven mad by beauty, such beauty that, taken away from it, you feel shrivelled and diminished, disoriented,” wrote Anna Mathews in 1965 in her book, The Night of Purnama, where she recounts her life in a small village in Bali at the foot of the sacred volcano Gunung Agung–before, during, and after the great eruption.

Nieuwenkamp probably felt “shrivelled and diminished” when separated from the island. None of his family–not even his devoted wife–ever agreed to travel with him to Indonesia. So, once back home, how could he ever start to explain his unique experiences, overflowing with such sensations and emotions? Was this why he failed to arouse any curiosity for Balinese culture in his grandchildren? Perhaps only through silence and solitude did he find his inner tranquillity.

Almost 100 years have passed since his arrival in my city. I slowly dug him out of the corner where he has lain hidden in hermetic Florence, and finally let him breathe again. Over the last decade, other events have taken place, one of which, in particular, would have made Nieuwenkamp smile.

Not many people know that, in July 1996, the Municipal Council of Florence adopted a Sister City Pact between Florence and Klungkung, the historic royal capital of Bali. This pact paid homage not only to W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp, but also to other inspired Florentines: the artist Emilio Ambron, whose paintings, drawings and sculpture were greatly influenced by Bali; and Emilio Pucci, whose Balinese designs launched a fashion line linking these two cultural centres of the world. On that occasion, the ailing Ambron donated several of his finest works to the Civic Museum of Klungkung. Now frequented by visitors from all nations and walks of life, the Ambron collection–a worthy representative of Florence and Italy–occupies the north wing of the museum and may serve to inspire new generations of artists.

While Balinese authorities have long since paid tribute to the “Pact,” the Florentine authorities have yet to officially celebrate this Indonesian bond. Even when tragedy struck Bali in October 2002 and 2005, with hundreds were killed and wounded, Florence remained silent. I wonder how much more time will have to pass before my city decides to acknowledge its adopted sister floating beyond the Indian Ocean? If almost a century had to pass for Nieuwenkamp’s work to come to light in Fiesole, there is still hope for what lies hidden in my hermetic Florence.