Sinossi in italiano

Il reportage focalizza l’attenzione su di un angolo della Terra che raggiunse il massimo del suo splendore nel 500 e che successivamente la storia ha dimenticato.

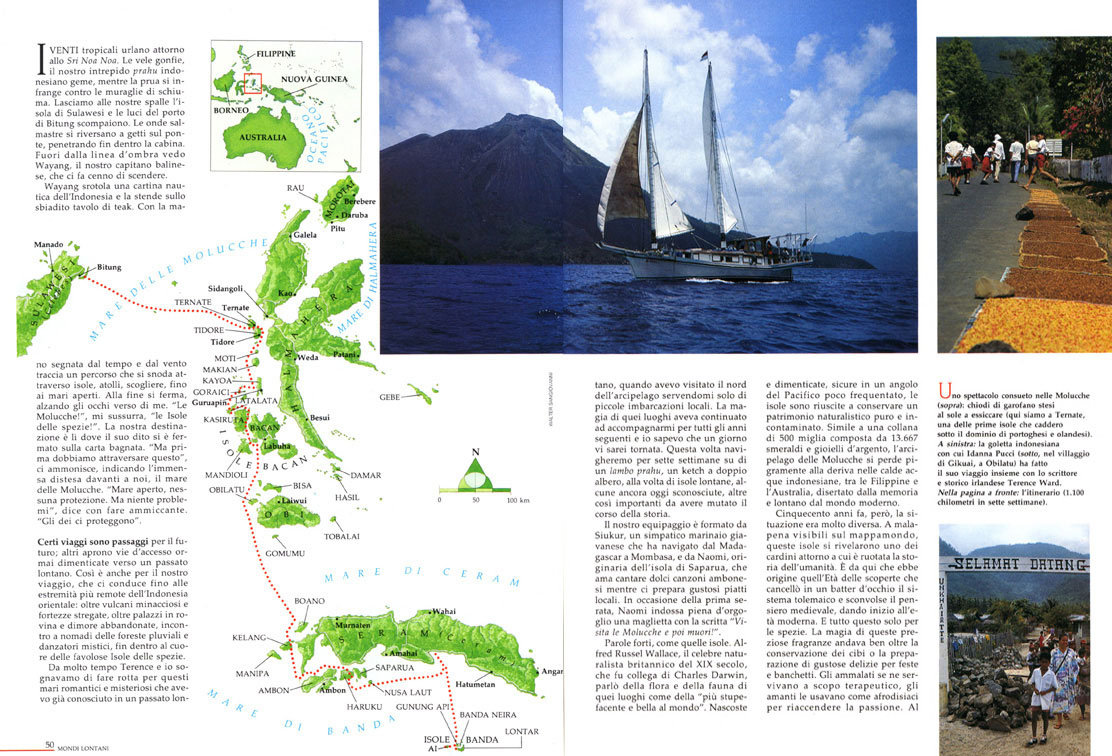

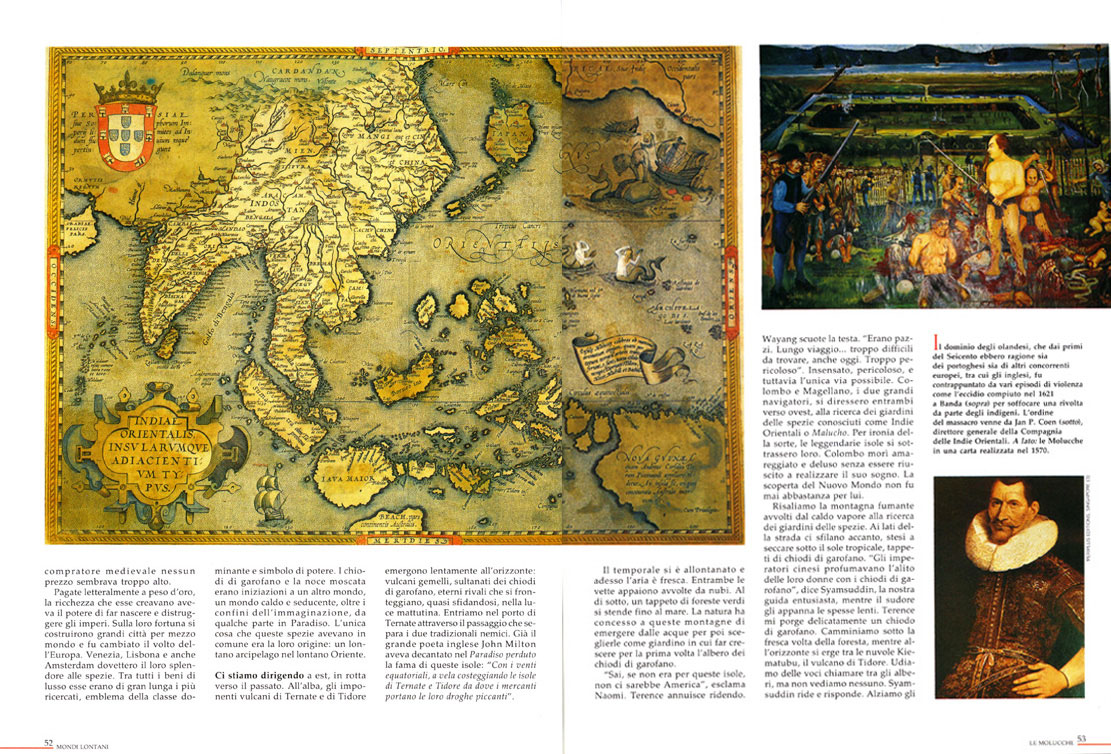

Nel settembre del 1993, Idanna Pucci and Terence Ward si imbarcano per un viaggio di due mesi alla volta delle Mollucche per esplorare le leggendarie isole delle spezie. Navigando su di una goletta indonesiana (prahu), iniziano la loro avventura a Ternate e Tidore, due isole di origine vulcanica, le quali in passato rifornivano il mondo di chiodi di garofano. Spostandosi verso sud, attraversano le isole di Makian, Kayoa, Goraichi, Bacan ed Obi e raggiungono poi Ambonya, isola che gli olandesi ribattezzarono “la regina dell’Oriente”. Quest’ultima aveva fatto da base alle operazioni della V.O.C., la compagnia olandese delle Indie orientali.

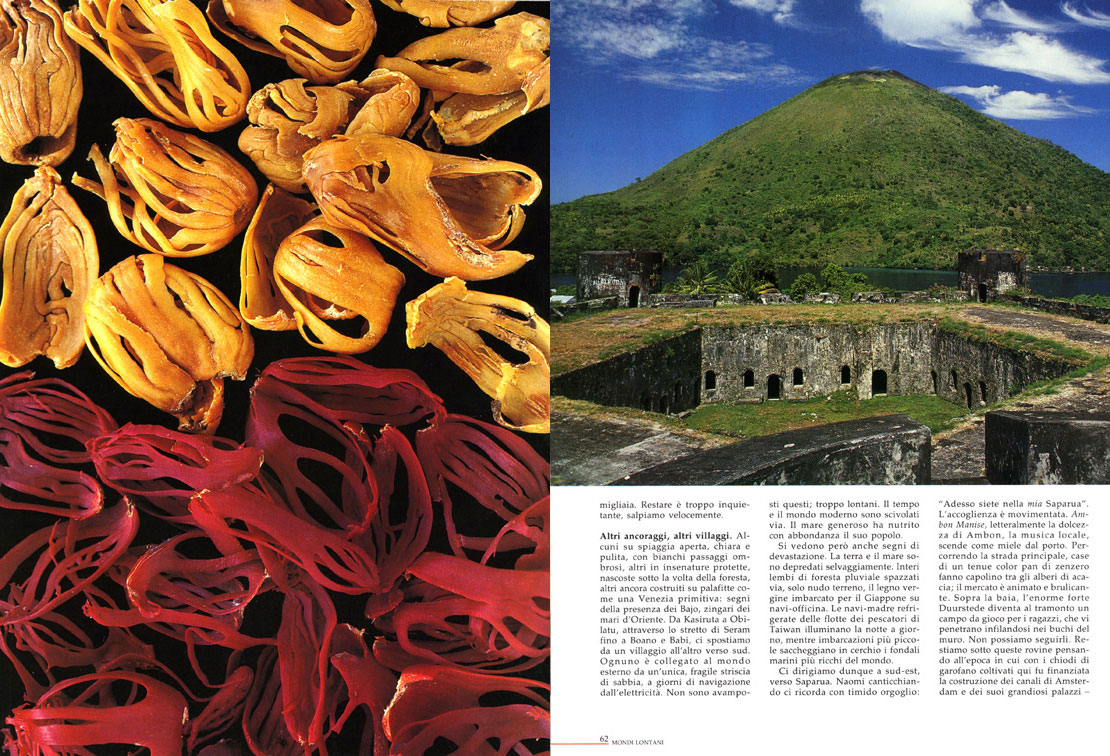

Fortezze e palazzi in rovina si susseguono assieme a giardini di spezie miracolosamente sopravvissuti, a foreste vergini tropicali e a banchi di corallo immersi in una flora e fauna che il celebre naturalista inglese Alfred Russell Wallace definì come “le più lussureggianti e ricche dell’intero pianeta.”

Da Ambonya, si raggiunge l’isola di Seram e, virando nuovamente verso sud, si giunge alla destinazione finale: il favoloso arcipelago di Banda, isole mitiche che in passato sono state le uniche a rifornire di noce moscata il mondo intero. E lì che si trova l’isola di Run che gli olandesi ottennero dagli inglesi in cambio di New Amsterdam, ovvero l’odierna Manhattan, nel 1667.

English translation

Dark tropical winds roared around us. Our brave Indonesian prahu, the Sri Noa Noa was groaning, her sails swollen, her bow crashing into walls of foam. Behind us, the harbor lights of Bitung vanished. Blasts of salty spray spilled over the deck, and down into the cabin. Out of the shadows, I saw Wayang, the Balinese captain motioning for us to come below. My hair dripped like black seaweed in the damp cabin while the flickering oil lamp swayed overhead to the pounding of the waves.

He unrolled a nautical map of Indonesia and stretched it over the faded teak table. Slowly his weathered finger traced a path across islands, atolls, reefs, into open seas. The wooden floor boards moaned. Finally he stopped and lifted his eyes to me. “The Moluccas, “he whispered, “the islands of spices”. There on the wet parchment where his finger rested was our destination. “But first, we must cross this”, he warned, pointing at the great expanse before us, the Molucca Straits. “Open sea, no protection. But no problem,” he winked,” the Gods are with us”.

Some voyages are journeys into the future. Others open forgotten doorways into the distant past. Ours became such a voyage, taking us to the far reaches of eastern Indonesia; past rumbling volcanos and haunted fortresses, decaying palaces and abandoned mansions, rainforest gypsies and dancing mystics – deep through the heart of the fabled Spice Islands.

For years, Terence and I had dreamed of sailing through these romantic and mysterious waters that I once visited long ago. Then, I had traveled only by steamers in the north but its magic spell stayed with me. I knew I would return. This time, instead, we would sail for 7 weeks on a “lambo prahu” or double-masted ketch to isles still unknown and others that changed the course history. Our crew included Sukur, a good humored Javanese sailor who had ranged from Madagascar to Mombassa and Naomi from Saparua who loved to sing her sweet Ambonese songs while cooking up tasty Moluccan dishes. That first evening she proudly wore her T-shirt that read, “Visit Moluccas Before You Die!”

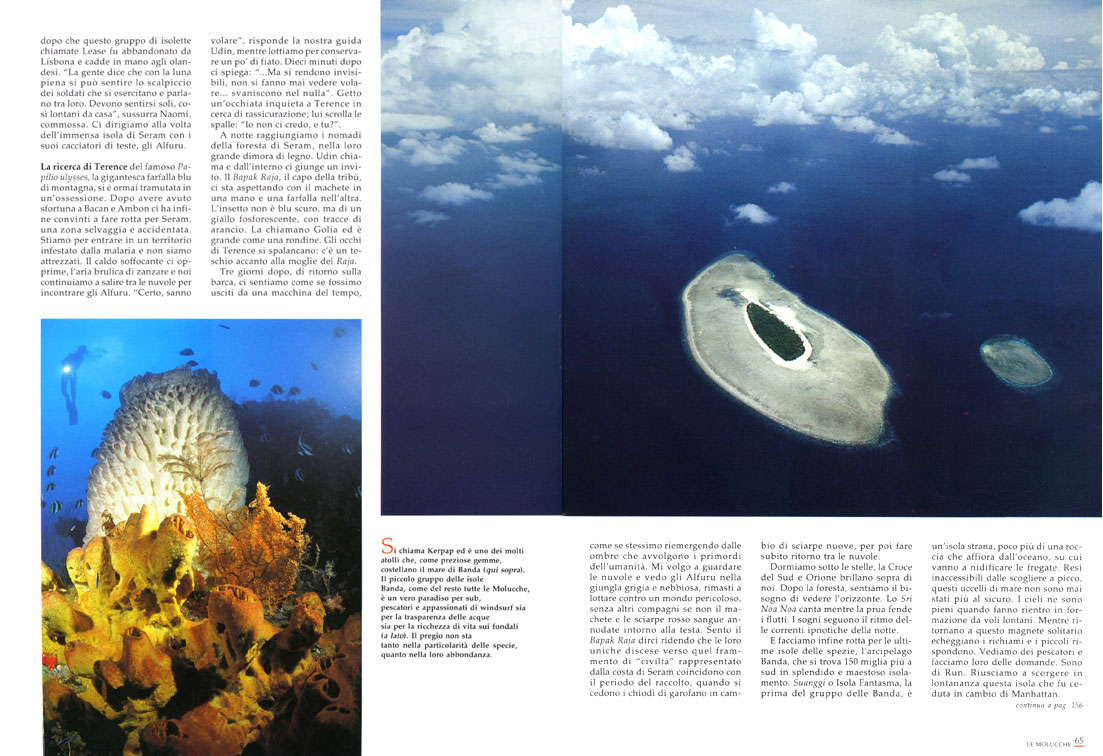

Strong words. Strong islands. Alfred Wallace, the famed 19th century British naturalist and colleague of Charles Darwin, once described the flora and fauna as “the most remarkable and beautiful upon the globe”. Remote and forgotten, in a rarely traveled corner of the Pacific, her natural world still remains pristine and intact. An archipelago of a thousand emerald and silver jewels strung loosely in a 500 mile chain, the Moluccas drift in warm Indonesian waters boardered by the Phillipines and Australia. Lost from memory, detached from our modern world.

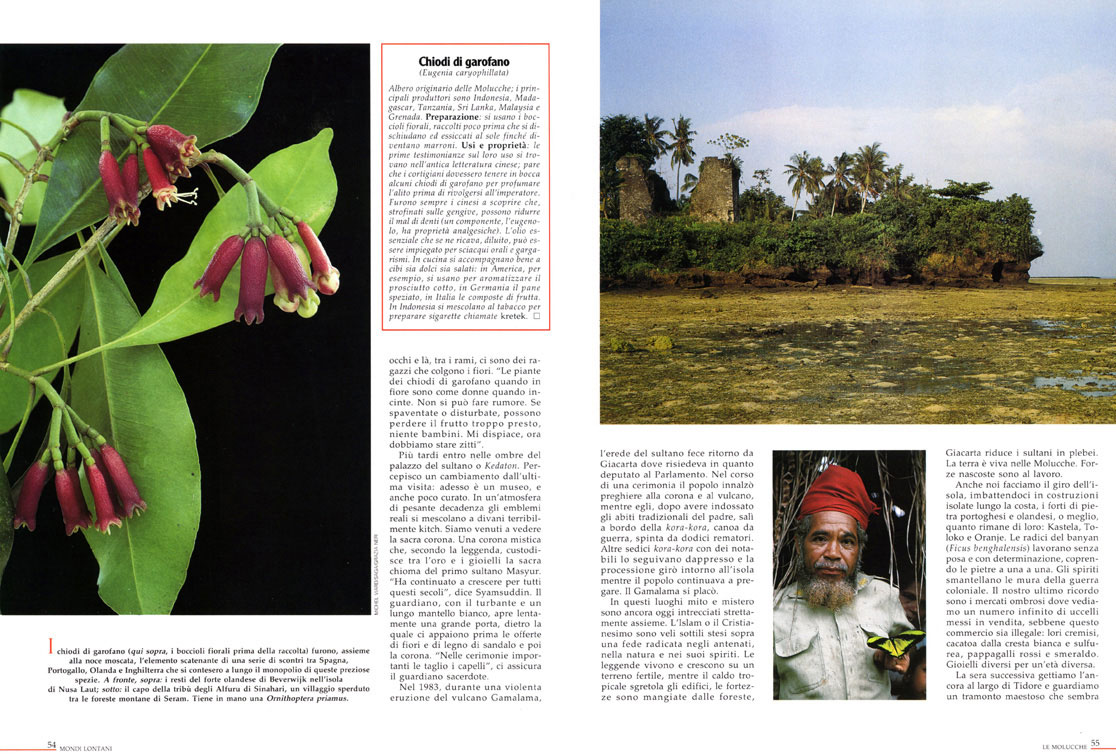

But, five hundred years ago, it was quite a different story. Barely visible on a global map, these islands sparked one of the most pivotal turning points in world history. They launched the Age of Discovery which overnight shattered the Ptolemeic and Medieval world views, giving birth to our Modern Age. It was all because of the spices. These fragrant jewels worked more magic than simply creating delicious tastes at feasts and banquests or preserving foods. For the sick, they served as thereuputic medicines and were even believed to cure the dreaded Black Death. For lovers they fueled passion, and were used as aphrodisiacs. For medieval consumers, it seemed that no price was too high to pay.

Worth, literally, their weight in gold, the wealth they commanded built and destroyed empires. Their fortune would build great cities half way across the world and changed the face of Europe. From Venice, to Lisbon and finally Amsterdam, each city owed its golden age to spices. Of all medieval luxury goods, they were the most highly prized. Collected like precious objects and presented as gifts throughout the castles of Europe, they were status symbols for the ruling class, emblems of power. Buds of cloves and chunks of nutmeg were initiations into another world, a warm and seductive world, somewhere further than could be imagined, somewhere in Paradise. The one thing that all these spices had in common was their origin: a distant archipelago in the distant East.

And we were heading east, sailing into the past. The night’s sleep was deep, rocked by the deep swells rolling against the Sri Noa Noa’s sides. At dawn the towering volcanoes of Ternate and Tidore slowly emerged on the horizon. Twin volcanos, clove sultantes, eternal rivals. facing each other defiantly in the morning light. We entered Ternate harbor through the narrow strait strait dividing the traditional enemies. In Paradise Lost the great poet Milton wrote of the islands fame, “On equinatical winds, close sailing from the isles of Ternate and Tidore, whence merchants bring their spicey drug.”

The air was cool, the storm had cleared. Clouds swirled around both peaks. Under the clouds, a carpet of green forests rolled down to the sea. It was nature’s gift that lifted these mountains out of the water and then chose them as the world’s only garden where the clove tree would grow.

“You know, if not for Maluku, there would be no America”, shouted Naomi proudly. Terence nodded and laughed. Wayang shook his head. “They were crazy. Long sail. Too hard to find, even now. Too dangerous.”

Insane, dangerous, but there was only one answer. The great discoverers, Columbus and Magellan, both sailed west, both in search for the spice gardens known as East Indies or “Malucho”. Ironically, the legendary isles eluded them. Columbus died in bitter frustration failing to realize his dream. The New World was not enough.

We climbed in the steaming heat up the smoking mountain to find spice gardens of clove trees. Along the way, we passed carpets of cloves drying in the tropical sun by the side of the road, their color ranging from fresh light green to a toasted brown.

“The emperors in China liked cloves to sweeten the breath of their women”, said Syamsuddin, our enthusiastic guide, sweating through his thick glasses. Terence gently handed me one. It was now cool walking under the forests canopy, off in the distance Tidore’s volcano broke through the clouds. We heard voices calling, but saw no one. Syamsuddin laughed, calling back into the trees. As we looked up, there hidden in the branches were young men picking the flowers. “Clove trees when blossom are like women when pregnant. No noise can be made. Men must take off hat when passing. If frightened or upset she may loose fruit too soon, no children. Sorry, now must be quiet.”

Entering into the shadows of the Sultan’s Palace or Kedaton, I felt the change since my last visit. Now, it was a museum, and half-heartedly kept. Royal regalia still mixed with a heavy atmosphere of decay and horridly kitch sofas. We had come to see the sacred crown. A strange and mystical crown which legend says holds the sacred hair of the first sultan Masyur amidst its jewels and gold.” And it has continued growing for centuries”, whispered Syamsuddin. The guardian, in turban and long white cloak, slowly opened the special door was opened. We gazed at the offerings of flowers and sandlewood and then on the crown. “In special ceremonies, I trim his hair,” the guardian priest assured us.

During a violent eruption of the Gamalama volcano in 1983, the sultan’s heir returned from Jakarta where he sits as member in Parliament. A festival was held, people prayed to the crown and the volcano, he donned his father’s traditional clothes and boarded a kora-kora war canoe with 12 rowers, another sixteen kora-kora followed

behind and the procession circled the island while the people continued praying. Gamalama stopped erupting and quieted.

Here mystery and myth are woven tightly together. Islam and Christianity are thin veils over a thriving belief in nature, its spirits and the ancestors. Legends live and grow on fertile soil. Buildings crumble in tropical heat and forts are swallowed by forests while sultans are reduced to common men by Jakarta. Unseen forces are at work in the Moluccas. Reality contains both what is seen and what is not. The land is alive.

We too circled the island on a different pilgrimage, stumbling through lonely Portuguese and Dutch stone forts along the coast – or what remains of them: Kastella, Toloko and Oranje. Overgrown with vegetation, the banyan roots were determined and working hard, slowly pulling out the stones, one by one as the spirits dismantled the colonial walls of war. Our last image was in the shadowed markets where we saw countless birds for sale, though this trade is illegal: sunbirds, crimson lories, white and sulfur crested cockatoos, red and emerald parrots. Different jewels for a different age.

We anchored off Tidore the next evening and watched a majestic sunset melt against the sky. The turbulent seas had calmed, the waves lapping on our sides. We saw the moon rising to the east. Naomi’s fish smoked from the fire on the beach. A sleepy village. Rustling palms. It was hard to believe this quiet island was the destination of Magellan.

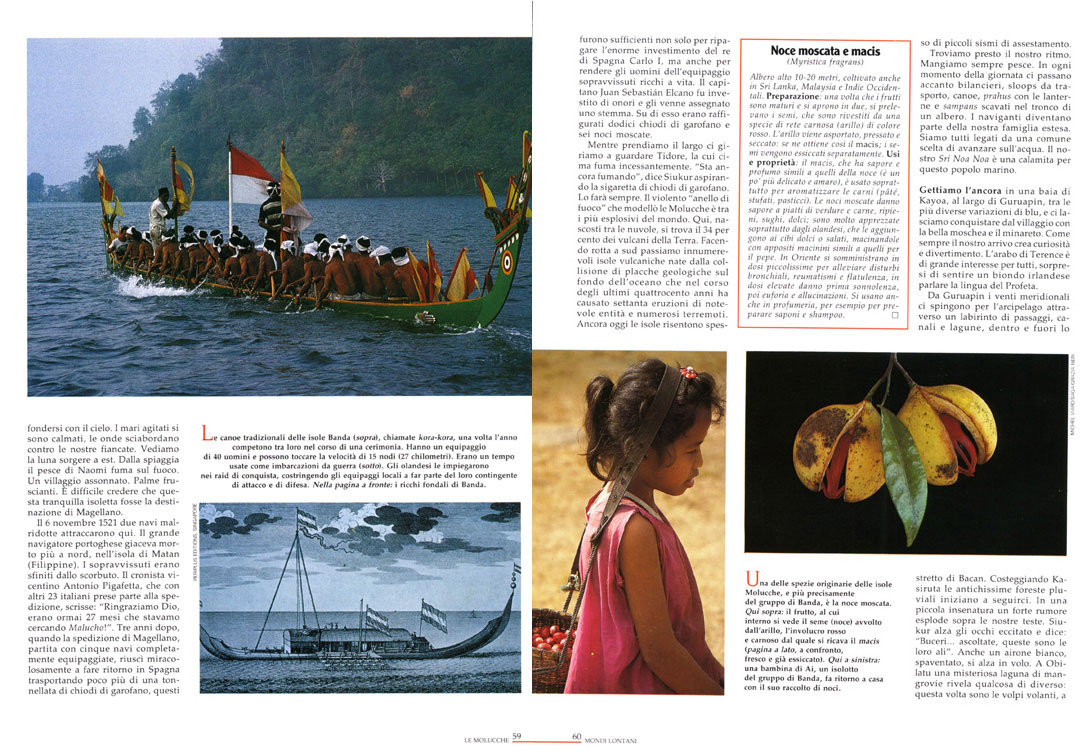

On November 6, 1521, two leaking ships anchored here.The great navigator lay dead on white sands further north. The starving survivors were ravaged by scurvy. Antonio Pigafetta, the chronicler wrote, “We thanked God, for we had passed 27 months in search for Malucho!” When Magellan’s expedition – with five fully outfitted ships and 230 men – finally limped home after three years with just over one ton of cloves, it was enough not only to pay back the Spanish king’s huge investment but also to make the 18 surviving sailors rich for life. The captain was awarded a coat of arms. On it was painted a dozen cloves and six nutmegs.

Looking back at Tidore as we sailed away, the fume from the peak was a steady stream. “It’s still smoking” said Sukur drawing on his clove cigarette. It always will. The violent “ring of fire” that sculpted the Moluccas is among the most explosive in the world. Sailing south we would pass countless volcanic islands born from clashing geologic plates on the ocean floor that have created seventy major eruptions in the past 400 years.

We soon found our rhythm. We ate fish everyday. People passed us by daily, in outriggers, trading sloops, canoes, lanteen-sailed prahus, and sampans carved out of one tree. It was strange, but sailors became part of our extended family. We were all related by our shared choice to float in wood over water. Our Sri Noa Noa was a magnet to this marine tribe.

Anchoring in a huge bay off Guarpin, amidst all different blues, we were lured to the village with its beautiful mosque and minaret. Each arrival created commotion and entertainment. Great stares and curiousity. Terence’s Arabic was of great interest to all, who were surprised to hear a fair Irishman speaking the prophet’s holy language.

The southern winds blew us through a labyrinth of passages, channels and lagoons, passing in and out of Bacan, and further down the archipelago. Along Kasiruta, the primieval rainforest began to follow us. In a narrow fjord, a huge sound echoed overhead, Sukur looked up excitedly saying, “Hornbills… listen, their wings” as three swoop over us. The king of the treetops, the hornbill with a bellicose screech that sounded like a runaway steam engine containing a litter of howling dogs. The largest birds of the forest, with outrageously long bills and striking black and white tail feathers, the whoosh of its wings could be heard a half a mile away. A white heron jostled by the noise, also took flight. In Obi Laut, a haunting mangrove lagoon exploded with something different, flying foxes, thousands of them. Too eerie to stay, we quickly pulled up anchor.

Another anchorage, another village. Some dwellings rested on open beaches, clean and neat with white shaded alleys, some in protected coves hidden under the forest canopy, others built on stilts over the water like a rustic Venice: sign of the Bajo sea gypsies of Indonesia. From Kasiruta to Obi Laut and Obi, across the Ceram Strait to Bonoa and Babi, we wandered south from one to another. Each connected to the outside world by a fragile, single strand, days sail from electricity. No outposts these, too far. Time and the modern world had melted away. The sea fed her tribes, her bounty plentiful.

But here were also signs of hunger. A monstrous clearing of land and sea. Cleared rain forests, red barren ground, the virgin hardwood shipped north to Japan on factory ships. Refrigerated mother ships of Taiwanese fishing fleets flood-lit at night as smaller boats circle, plundering the world’s richest fishing grounds. Clean technology leaves little behind.

So we headed south-east, passing Ambon, in and out of Saparua, and on to the primeival island of Ceram: deep into its cloudforest, high in the mountains that its notorious headhunters, the Alfuru, called home. My search for the famous Papilio Ulysses, the huge cobalt blue mountain butterfly, had now become an obsession. After no luck in Bacan or Ambon, I had convinced the skipper to sail to this wild place. Our trek was deep into malaria infested country. We weren’t prepared. Smothering heat blanketed us, mosquitos swarmed, and into the clouds we climbed to meet the Alfuru.

“Of course, they can fly,” answered our guide, Udin, as we struggled out of breath. Ten minutes later, he explained, “but they’re shy, they don’t like us to see them fly, so they become invisible. Vanish.” I looked over to Terence for a sanity check. He shrugged his shoulders in agreement, “I haven’t seen them, have you?”

By nightfall, we had reached the hornbill more secretive cousins, Ceram’s forest gypsies, in their long spirit house. Udin called out, and from inside came an invitation. The Bapak Raja or tribal chief was waiting – with his machete and a butterfly. Not dark blue, but a phosphorescent yellow, with traces of orange. He called it Goliath. It was the size of a bird. My eyes were open wide, the size of a skull hanging next to the Raja’s wife. I dipped my legs into the river; they burned like hot coals.

Back on the boat, three days later, we felt as though we had climbed out of a time capsule, emerging from the shadows of man’s earliest beginnings. Looking back to the clouds, I could still see the Alfuru in the grey-misted jungle struggling in a dangerous world, with no possessions except machetes and the blood-red scarves tied around their heads. I heard Bapak Raja’s laugh when he told us that their only trips to the thin scrawl of “civilization” below on Cerams’s coast was at harvest time as they traded in their harvested cloves for more scarves and returned back to the clouds.

That night we slept under the stars. The Southern Cross and Orion’s sword hung overhead. Our eyes needed horizons after the forest. The Sri Noa Noa was singing as her bow cut cleanly through the swells. The hypnotic currents doubled our dreamtime.

And we sailed for the ultimate “spice islands”, the Banda Archipelago that lay 150 miles south in splendid isolation. Suanggi or “Phantom” was a strange island, a virtual rock lifting out of the ocean in the Banda group, a birthing sanctuary for frigate birds, inaccessible and with vertical cliffs. These birds of the seas had never been safer. And they could feel it. The skies were full of their wings returning to this lonely magnet from distant flights in formation. Calls echoed, their babies answered back.

We spotted fisherman and asked them questions. They came from Run. We could see it in the distance: the island once traded for Manhattan. In 1667 the Dutch did the unthinkable. Desparate to rid the British from the nutmeg isles of Banda, they traded away their colony in New Amsterdam, which immediatley was christened New York. “The Big Apple” for nutmeg and cloves.

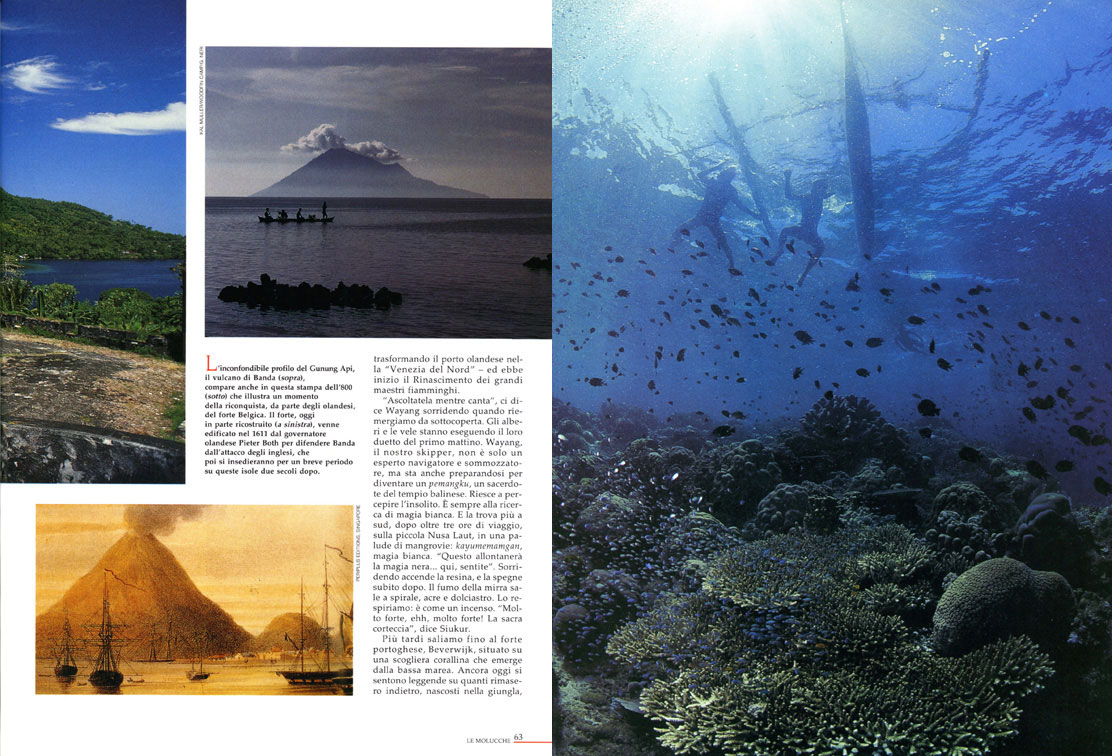

“Smell that?” Wayan asked over coffee “sweet, no?” The wind had changed. The salt had gone. “That is Sri Noa Noa. Sweet fragrance of land, an old Polynesian word.” It was sweet, and the land even looked like Polynesia. The Gunung Api or fire mountain reared its angry head, rising like a beacon in the emerald waters. We entered the strait, green arms sheltered us in the lagoon. Our last crossing was over.

Nutmeg, mysterica fragrans, is a truely magical spice, so passionately loved that in the 17th and 18th centuries people carried their own silver nutmeg graters to add the freshly ground spice to their food or mulled wine. One of nutmeg’s remarkable constituents, mystristicin, can induce euphoria and hallucinations. Certainly something worth warring over. But the ultimate irony was that the Bandanese had never eaten the golden fruit or even used nutmeg in any of their food.

We watched a ceremony that day. The dance costumes were treated like pusaka or sacred heirlooms. We looked as each was taken out from a special room that had an altar of offerings where incense burned over the Islamic holy book, the Koran. Before the festivities, holy men took offerings to several sacred locations: river, stones, and trees where they worshipped. Then a spirited war dance, the cakalele, began. Five men dressed like 16th century Portuguese explorers in medieval outfits of red and black, wearing curved steel helmets, topped by bird of paradise plummage, appeared and started dancing theatrically for the crowd. We then heard drums and men chanting. Turning to the lagoon, we saw virile arms pumping like pistons to the cadence of the drums in their kora-kora canoes racing around the island. The two canoes manned by 40 men flew through the water at 15 knots.

There are rare settings on this planet where superlatives fall flat. Banda is such a place. In the Molucca chain, they are, without a doubt, the prize jewel. Until the 19th century, this small archipelago was the world’s only source of nutmeg and mace. A cluster of nine lush, green islands dotted with fortresses and spice gardens that surfaced from the depths of the Banda Sea.

Now the past is lost in the scent of kenari, nutmeg and cinammon trees. The once lavish port of Bandaneira remained drowned in its deep slumber. A Mediterranean feel floated over this “gone with the wind” stage-set, its two lazy streets lined with delicately wrought-iron street lamps with nutmeg designs in front of old planters’ marble mansions in gentle decay. Docked at the tiny port of Bandaneira, our Sri Noa Noa was ready to leave.

Our odyssey was now ending, and we gave our farewells over a glass of tuak to our memorable host, Des Alwi, the uncrowned “king” of Banda. He summed up his islands with great humor, “Difficult to get here, harder to leave!” We paused in the milky twilight, stared up to the smoking volcano, and walked back to the boat to tell our captain to sail off without us.